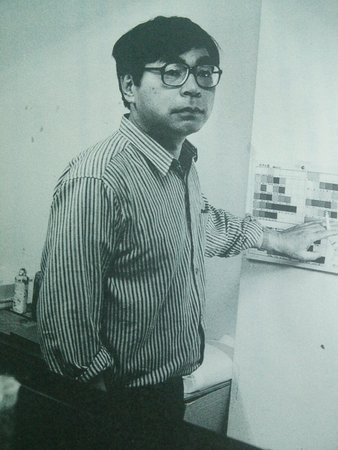

Many people around the world love the films of Japanese director and Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. Which is typically what happens when you have My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away all in your filmography. The man has a tendency to tell life-affirming stories with beautiful animation and a style that is unmatched in the world of cinema. So how did he get his start in the film industry and become such a master of animated storytelling?

Hayao Miyazaki was born in Tokyo City in 1941, the son of the director of a World War II rudder manufacturing company called Miyazaki Airplanes (although while Miyazaki’s father contributed to the war effort, he was actually discharged from the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII when he chose to stay with his wife and child rather than fight). As you might imagine with many Japanese children who were raised in the 1940s, Miyazaki’s earliest memories are of city debris and wiped out streets. In fact his family had to evacuate the city of Utsunomiya for the city of Kanuma in 1945 due to the U.S. bombing that region. Miyazaki was forced to grow up from a pretty young age, and not just because of the war. He and his siblings were tasked with domestic duties after his mother suffered spinal tuberculosis.

But Miyazaki had ambitious aspirations. While in junior high, he wanted to be a manga artist, even though he seemed to be more skilled at drawing planes and tanks than drawing human figures. At the same time he often went to the movies with his cinema loving father. But more than manga and cinema, it was Miyazaki’s interest in animation that really opened up his imagination, sparked in particular by the 1958 film The White Snake Enchantresses (a film Americans knew as Panda and the Magic Serpent), which was the first feature-length anime film in color and which left a profound impression on a young Miyazaki, prompting him to pursue his passion for creating art that affirmed positivity in the world and attempt to move people the way that film had moved him.

Miyazaki’s professional introduction to the animation industry came in 1963 when he was hired at Toei Animation (the studio behind White Snake Enchantress), who was making their TV animation debut that same year with Wolf Boy Ken, a series that ran from 1963 to 1965 on the TV network NET and was co-directed by future Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, who struck a friendship with Miyazaki during their years at Toei. Miyazaki worked as an inbetweener on that show, but Toei also sent Miyazaki to work on their 1963 feature film Doggie March and their 1965 feature film Gulliver’s Travel’s Beyond the Moon, a sci-fi infused adaptation of the Jonathan Swift novel Gulliver’s Travels and one of Toei’s first anime films to stray from Japanese mythology.

Miyazaki was a major asset in Gulliver’s development, even making suggestions about the ending that made it into the final film. But for the most part Miyazaki was unsatisfied by the work of inbetweening and he obviously longed to express his artistry more fully. Luckily he moved from inbetweening to key animation on several Toei productions in the late sixties, including the TV shows Fujimaru of the Wind (1964-65), Hustle Punch (1965-66), Sally the Witch (1966-68) and Rainbow Sentai Robin (1966-67). But still longing for creative fulfillment, Miyazaki took matters into his own hands and volunteered to work as a designer, concept artist and animator on Toei’s 1968 feature and Isao Takahata’s feature film directorial debut The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun.

That film went on to receive positive reviews and it was also the first sign that there was something magical about Miyazaki and Takahata’s collaborations. Even Tokyo-based American film critic Mark Schilling singled the film out as the first commercial effort by an animation studio to surpass Disney in quality as he compared it to the The Jungle Book, which was released a year earlier. Miyazaki and Takahata both worked on Horus under the mentorship of animator Yasuo Ōtsuka, who not only animated on The White Snake Enchantresses but also classic anime films like Magic Boy and Alakazam the Great, and whose approach to animation was a huge influence on Miyazaki.

Despite many calling Horus a pivotal step in the evolution of the animation medium, it received little promotion and therefore made little money, and Miyazaki continued animating for Toei.

Miyazaki provided key animation for two magical girl anime shows, Himitsu no Akko-chan (1969-70) and Sarutobi Ecchan (1971-72) and was a key animator, storyboard artist and designer on several more Toei films, including the 1969 musical comedy The Wonderful World of Puss ‘n Boots and the 1969 sci-fi film Flying Phantom Ship (for which Miyazaki designed the giant robot), as well as the adventure comedy Animal Treasure Island and the Arabian fantasy Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves both released in 1971. Miyazaki also made a rare venture from Toei to animate on Tokyo Movie Shinsha’s TV adaptation of Moomin, which aired from 1969 to 1970 on Fuji TV.

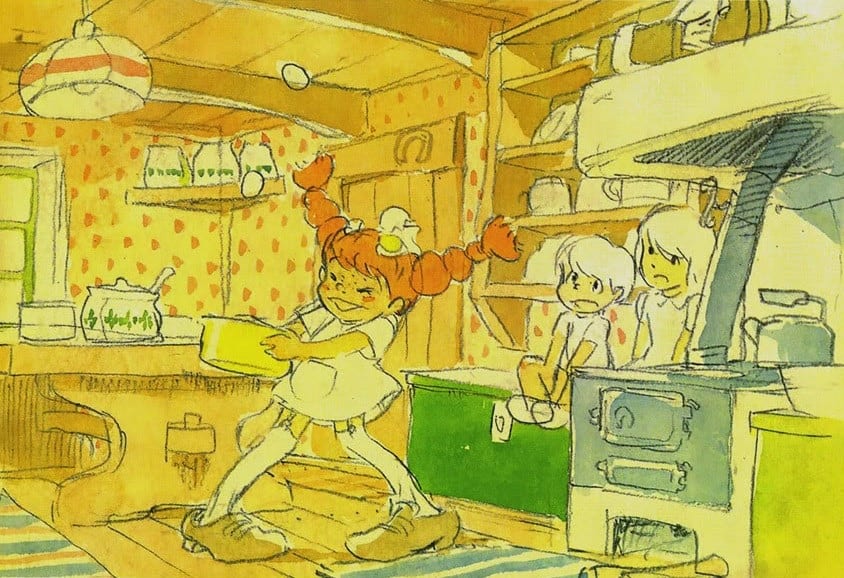

Due to the lack of creative autonomy at TV animation studios during that period, Miyazaki finally left Toei in 1971 along with the equally unsatisfied Isao Takahata and another Toei animator named Yōichi Kotabe (Kotabe would later go on to be hired at Nintendo, for whom he would illustrate box art for Mario games and be an animation supervisor on several Pokémon films). Once the three artists left Toei they intended to push the animation medium forward without creative limitations. One idea that appealed to Miyazaki was to adapt Pippi Longstocking, although that project ultimately went unproduced when Miyazaki and Tokyo Movie Shinsha president Yutaka Fujioka travelled to Sweden to meet Pippi Longstocking author Astrid Lindgren but were unable to make a deal with her. Although Miyazaki was able to recycle some of his Pippi Longstocking concept art elsewhere, including for a couple of short films he wrote, designed and animated with direction from Isao Takahata: Panda! Go, Panda! (1972) and Panda! Go, Panda! The Rainy-Day Circus (1973).

Miyazaki did not abandon the medium of television though. Most famously in his post-Toei television career, Miyazaki made his directorial debut on the anime series Lupin the 3rd Part I (1971-72) based on the popular manga by Monkey Punch about a slick thief who constantly escapes the law. Miyazaki would return for Lupin the 3rd Part II in 1980, although you wouldn’t know it from reading the credits because he went under the pseudonym “Tsutomu Teruki” for that season.

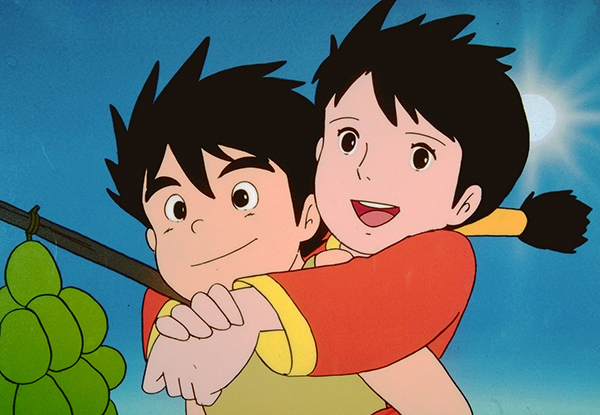

Miyazaki also did design and layout work under the direction of Isao Takahata on the TV series Heidi, Girl of the Alps in 1974 for animation studio Zuiyo Eizo, but Miyazaki mostly spent his career in the late seventies working on TV series for Nippon Animation, including providing design and layout for 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother (1976) for which Miyazaki took inspiration from research trips to Italy and Argentina, providing key animation for Rascal the Raccoon (1977), directing episodes of Future Boy Conan (1978) for which he got to indulge in his love for what are seen today as common Miyazaki themes, airplanes and environmentalism, and he provided design and layout for Anne of Green Gables (1979).

The last few times Miyazaki worked on a project that wasn’t his own before he founded Studio Ghibli were with Tokyo Movie Shinsha when he animated for the 1982 feature film Space Adventure Cobra: The Movie and when he directed episodes of the 1984 TV series Sherlock Hound. However the path that led him to the creation of Studio Ghibli came in 1979 with the release of The Castle of Cagliostro, the movie that changed the course of Miyazaki’s career and which I will discuss in my next article.