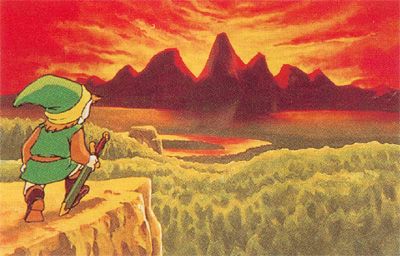

I don’t know if I’ve ever said this in any of the nine years I’ve been writing about video games on this blog, but it’s my opinion that Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda series is definitively the best video game series of all time. I’m going to write a series of blogs throughout 2026 (the year of Zelda’s 40th anniversary) to detail what makes the series so great but the basic reason why I love it so much is because from the very beginning it took pre-existing adventure and RPG formulas and executed them to perfection with a brilliant blend of mettle-testing monster battles, gradual but rewarding skill growth, a wide variety of weapons, tools and treasures and a true sense of exploration and discovery. It felt like the game that every action-adventure game in the past was leading up to, and it has one of the best track records for quality I’ve ever seen in a game franchise that has been around since the eighties, because as the series continued through the decades it has always managed to evolve and find new ways to remain fresh and interesting.

The Legend of Zelda made its debut in Japan in 1986. The game takes place in the kingdom of Hyrule (the people of Hyrule are known as Hylians). Hyrule’s entire providence is centered around an object called the Triforce. The Triforce is an important artifact and a sacred symbol in Hylian history that most Zelda game plots revolve around. In later games as the lore is expanded, it is revealed that the Triforce was left behind by three deities known as the Golden Goddesses (Din, Nayru and Farore) and that the Triforce was entrusted to a divine entity named Hylia, who was then reborn in mortal form as Zelda, the first princess of Hyrule and sworn protector of the Triforce. The mortals who occupy Hyrule have since gone on to worship and honor Hylia, not only by naming the kingdom after her but by naming every princess with royal Hylian blood after the first Zelda. Which is why every princess in every Zelda game has that name, despite many of the games taking place generations apart.

The Triforce is divided into three triangles: the Triforce of Power, the Triforce of Wisdom and the Triforce of Courage. Together they can grant any wish to any mortal. This leads a dark prince named Ganon to invade the kingdom of Hyrule and hunt down the Triforce. He manages to obtain the Triforce of Power and take over Hyrule Castle, but right before Ganon’s henchmen come for Zelda, the princess splits the Triforce of Wisdom into eight pieces and sends them flying across the kingdom to escape Ganon’s grasp. Zelda then sends her nursemaid Impa to find the legendary hero (the one who holds the Triforce of Courage) who is destined to save Hyrule from Ganon. After holding Zelda captive, Ganon’s henchmen almost get Impa too, but she is saved by a boy in green garments named Link. Convinced that he is the legendary hero, Impa convinces Link to reassemble the eight pieces of the Triforce of Wisdom and, with the combined forces of Zelda’s wisdom and Link’s courage, journey to Death Mountain to defeat Ganon.

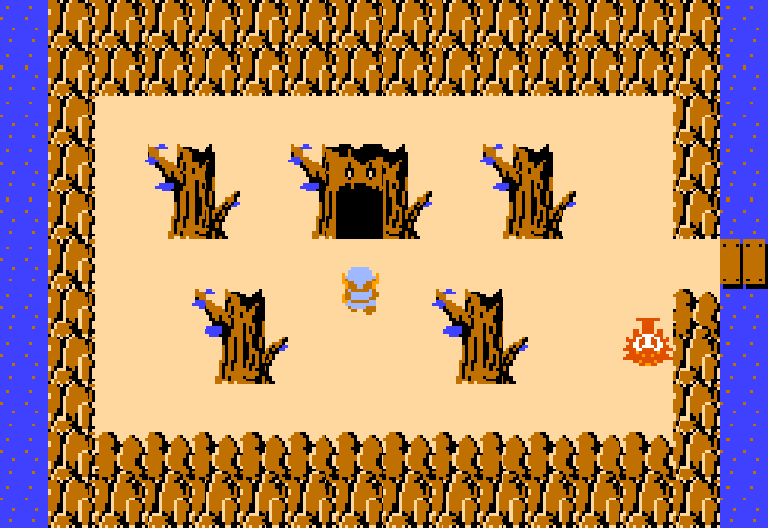

The Legend of Zelda incorporates traditional elements of role-playing games but is mostly action and adventure-focused. Just like most RPGs the game is viewed in a top-down bird’s eye view perspective, which really gives you a strong sense of freedom as you explore the world. Famously, your starting location literally gives you three different paths to choose from.

Your only starting item is a shield, but throughout the game you will collect many weapons and tools, including a sword, a bow and arrow, bombs, a boomerang, a power bracelet, a magic rod and other useful items, many of which can be found in the eight dungeons where the Triforce fragments are hidden. Your life meter is represented by three hearts, which will deplete as you take damage from monsters, although sometimes defeated monsters will leave behind hearts that will restore your health. If you encounter a fairy, it will restore more health, and you can also increase your heart count from three to four and so on the more heart containers you find. In addition to hearts, defeated enemies may also leave behind a diamond-shaped currency known as Rupees, which can be used to buy items at shops. All these things can also be found within the puzzle-filled labyrinths scattered across the land (and every defeated boss will leave behind a heart container). A secret ninth dungeon where Ganon resides will appear on Death Mountain after you restore the Triforce of Wisdom, although he can only be defeated with silver arrows.

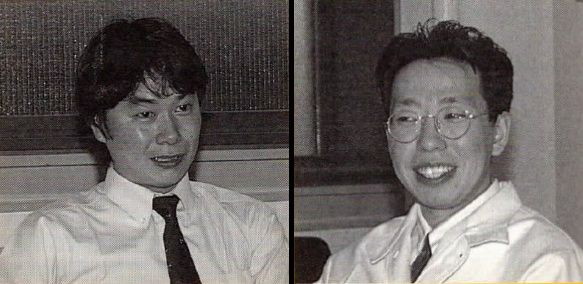

The Legend of Zelda was directed and designed by Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka, the same team who had massive success a year earlier with Super Mario Bros. (1985), which was being developed at the same time. Zelda was Miyamoto’s way of expanding the concept of world exploration beyond the platforming limitations of Super Mario Bros., essentially by allowing players to have more freedom and by giving them a mini interactive playground in their own home, inspired in part by Miyamoto’s own childhood exploring the wilderness of Kyoto where he grew up, sometimes making exciting discoveries (including the time he discovered a waterfall). Even the maze of sliding doors in his own home was a source of inspiration for the maze-like dungeons Link explored in the game. This feeling of freedom and discovery was the feeling Miyamoto meant to convey to the player.

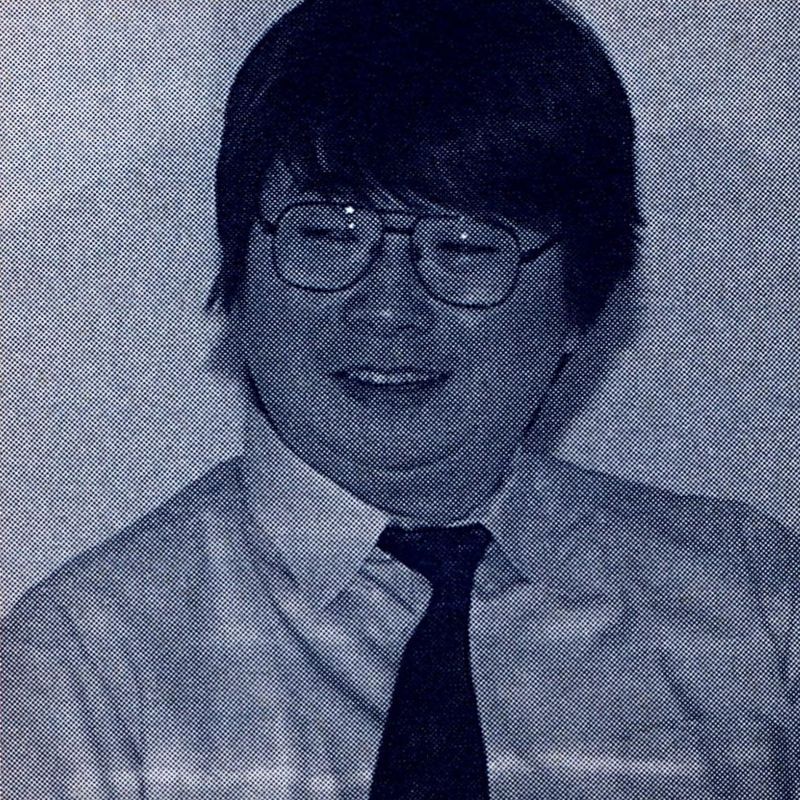

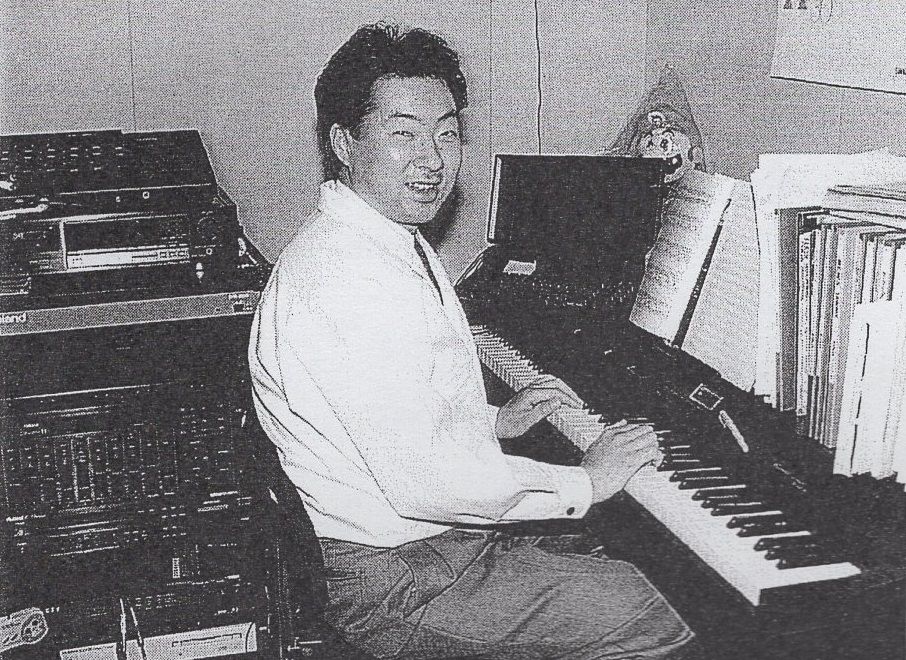

Early concepts for the game involved time travel between the past and the future (something that later Zelda games would explore), which is why the character was named “Link.” In this version of the game, the Triforce was actually electronic instead of magical, but this was scrapped in favor of a straight medieval fantasy. The story, as well as the script, was written by Takashi Tezuka and he took inspiration from fantasy books like The Lord of the Rings while creating the world of Hyrule, with anime writer Keiji Terui fleshing out the details. Much of the game’s ambitious and elaborate programming was handled by Toshihiko Nakago with Yasunari Soejima and I. Marui. Super Mario Bros. composer Koji Kondo would also return to compose the music for this game, with the biggest highlight being the field theme you hear at the start of the game (and throughout most of it) which came to be known as the Legend of Zelda theme song.

The game’s namesake, Princess Zelda, got her name because Miyamoto liked the glamorous sound of Great Gatsby author F. Scott Fitzgerald’s socialite wife and jazz age flapper Zelda Fitzgerald, who, like the princess of Hyrule, was also a famous and beautiful woman.

The Legend of Zelda not only marked a significant point in Nintendo’s software development history but also in the company’s hardware development history, because it was the launch game (along with a re-release of Super Mario Bros.) for Nintendo’s floppy disk-based version of the Famicom known as the Famicom Disk System, which was a console with more affordable data storage, better audio quality and for the first time, the ability to save your game’s progress, which was definitely necessitated by the huge size of open world games like The Legend of Zelda and Metroid and later RPGs like Final Fantasy.

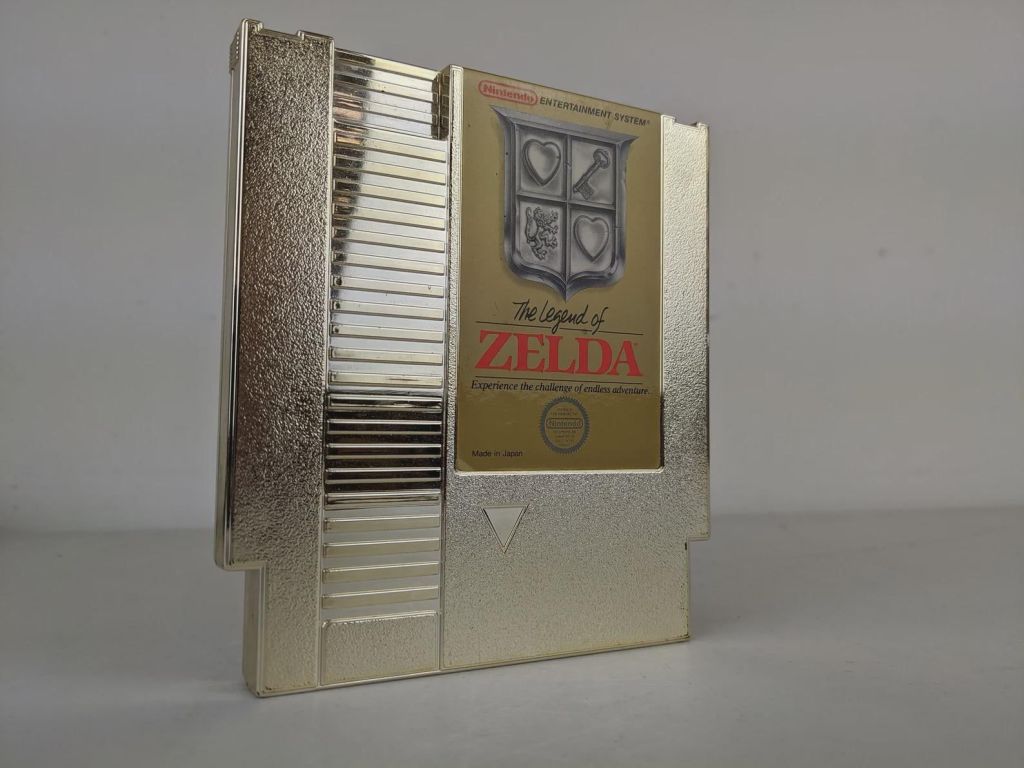

Although despite the revolutionary development and now standard practice of the save feature, the Disk System itself didn’t really catch on. It was undone by high costs, long load times and disk cards that were too fragile and easily damaged, which led to the cancellation of an American release. Although The Legend of Zelda was later localized and released in the U.S. for the cartridge-based NES instead, with built-in save feature intact, thanks to the battery-powered RAM of the cartridge-based memory management controller chip (MMC1), which also allowed for expansive world exploration. The NES cartridge was even gold-colored as opposed to the grey cartridges of other NES games.

Whether it was released on the Famicom Disk System in Japan or the NES in America, The Legend of Zelda received hugely positive reviews, from the gamers who made it one of Nintendo’s best sellers (and the first NES game to sell a million copies) to the critics who praised its huge overworld, wide variety of weapons, tough but fair difficulty level, clever dungeon-based puzzles, great music, beautiful graphics, beautiful presentation and smooth technical performance. And the ability to save your progress was just as groundbreaking as the moment Mario first jumped on screen.

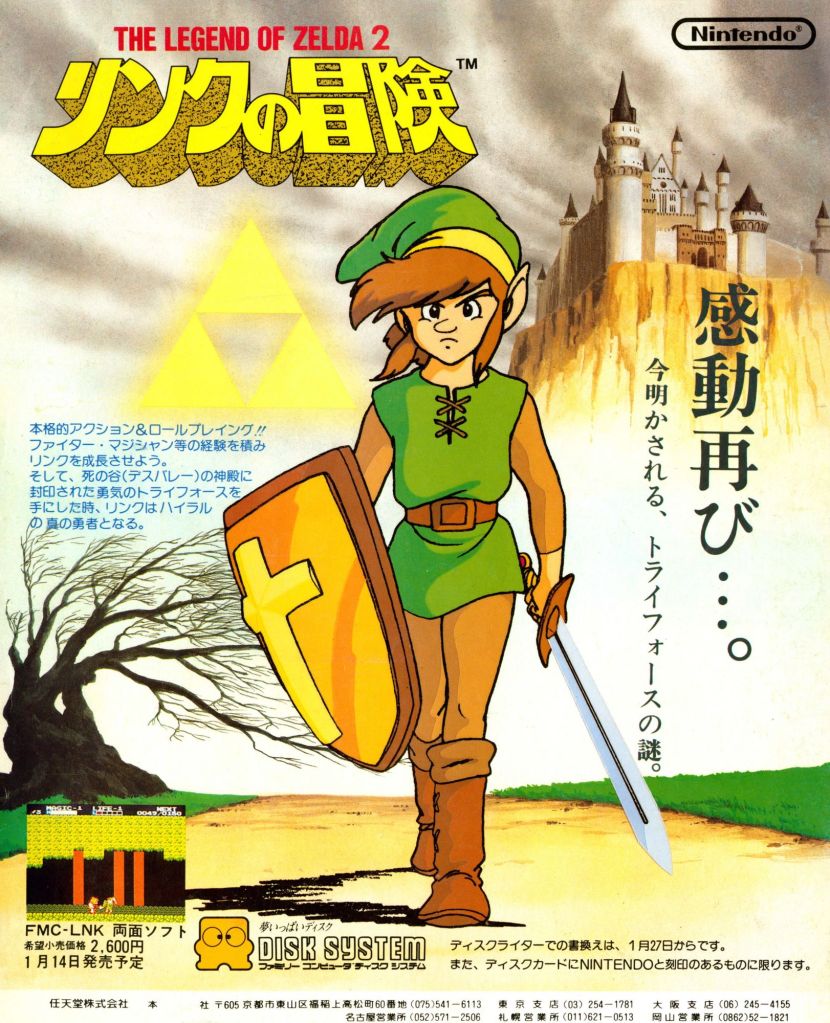

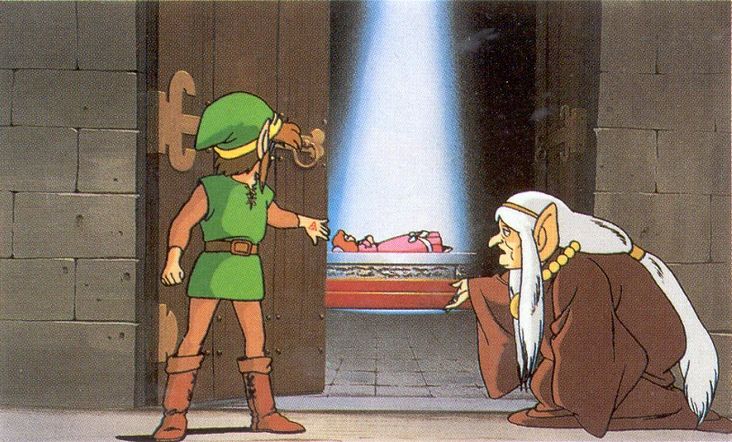

As huge as Super Mario Bros. was, many people thought The Legend of Zelda was Nintendo’s crowning achievement. Which led to a sequel titled Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, released in Japan for the Disk System in 1987 and in America for the NES in 1988. A direct sequel set a few years after The Legend of Zelda, this game told another story in which Link must go on a quest to save a princess named Zelda who was put under a sleeping spell. Only this Zelda is the FIRST Zelda (aka the mortal form of Hylia) and it turns out she was cursed under that sleeping spell and frozen in time for multiple generations!

Zelda II introduced some core additions to the Zelda mythology, including the first official confirmation that Link holds the Triforce of Courage, as well as the introduction of Dark Link, a shadow clone of Link who makes frequent appearances throughout the Zelda series in one form or another.

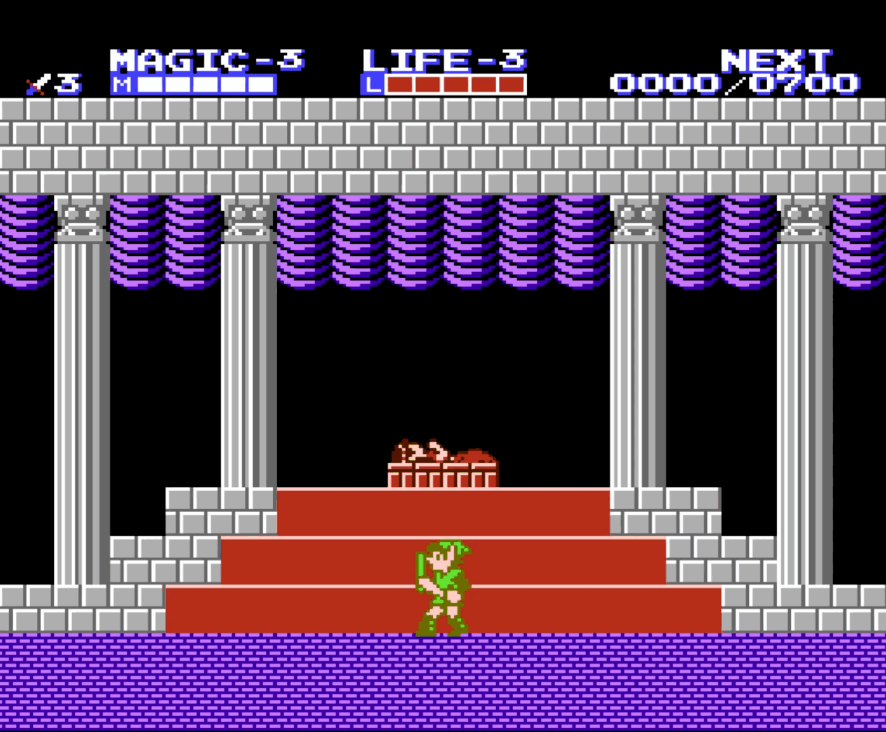

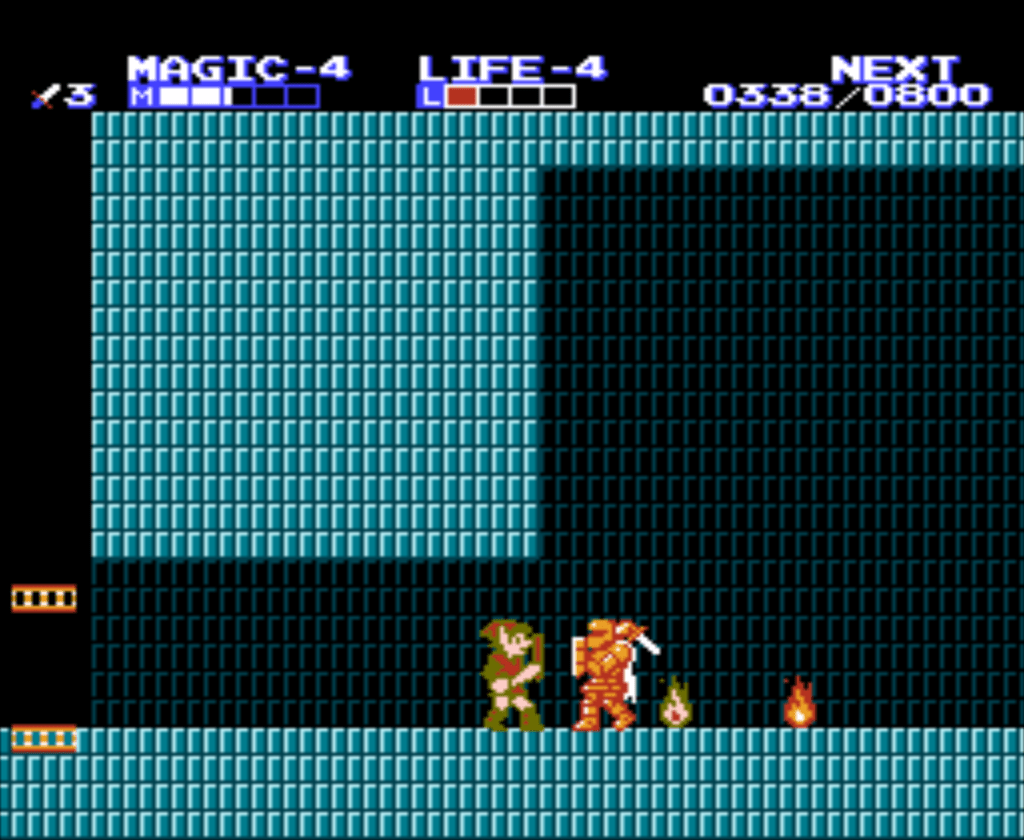

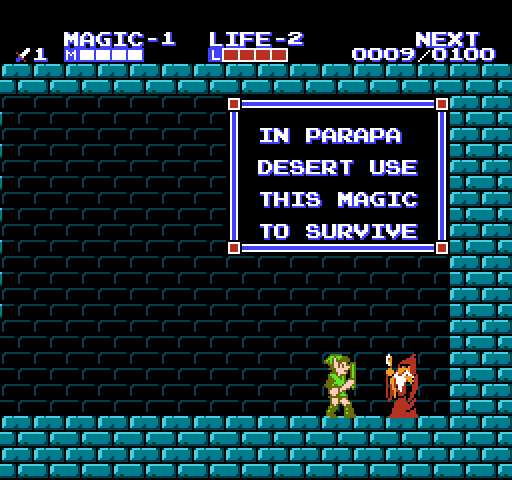

Zelda II also received critical and commercial success, although it’s not the widely beloved classic the first game is. That may partly be because of the radical turn it takes from the first game. This time the action all takes place in a Castlevania-style side-scrolling format. The game also features more interaction with non-playable characters such as townsfolk, and a more RPG-like experience point system which increases the more you defeat enemies, slowly enhancing Link’s attack (offense), life (defense) and magic (the size of your magic meter, which depletes the more you cast spells).

Shigeru Miyamoto intentionally made Zelda II different from the first game, even assembling a completely different team of programmers who were influenced more by the combat mechanics of games like Irem’s 1984 arcade beat-’em-up Kung-Fu Master and the role-playing mechanics of Chunsoft’s Dragon Quest (1986). Zelda II is also a lot more challenging than The Legend of Zelda, although many critics defend the difficulty as fair, which is why the game still has a passionate fan base to this day, despite it being seen nowadays as a lesser entry in the series compared to the heights the series would reach in the future, which I will chronicle in detail in the coming months.