I already wrote an article about television producer Norman Lear and his huge influence on sitcoms with shows like All in the Family and Sanford and Son. In short, his shows changed the language of mainstream comedy. But before Archie Bunker and Fred Sanford came along, there were a lot of other sitcoms that slowly broke ground in other ways. Some of which were arguably even more controversial, especially due to the period of history in which they aired. As taboo as All in the Family was, CBS would not have greenlit it if they didn’t have some faith that it had a chance of succeeding, and it just so happened that we were ready for a show like that in 1971. But comedy has also been the medicine that makes it easier to discuss serious subjects and break new ground long before that.

Amos ‘n’ Andy (1951-53, CBS)

This show started out as a popular radio show that ran from 1928 to 1960 and was created, written and performed by two White men named Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll who voiced two Black men named Amos and Andy. The show centered around a community of Black characters living in Harlem in New York City, but the way the characters talked and behaved was rooted in minstrel shows.

Just to go on a slight tangent for the sake of context, minstrel shows were an old form of entertainment that often featured White performers in blackface depicting Black people as uneducated and simplistic. There was no attempt by White people to add any depth or authenticity to minstrel shows. The sole purpose was just to lampoon the stereotypes of Black culture for the amusement of other White people, and it was a hugely popular form of entertainment for reasons that even as a dated practice boggle the mind (almost as if dehumanizing people was the most hilarious thing in the world in early 20th century America).

Amos ‘n’ Andy was adapted to television on CBS in 1951 and to Gosden and Correll’s credit, they made the bare minimum of a smart choice and decided to cast actual African-American actors in the title roles this time. Which brings me to the obvious reason why I included the show in this list. Of course while it was groundbreaking for being the first sitcom in TV history to be led by Black actors, that didn’t mean that the stereotypes were toned down, and in fact the show immediately drew the ire of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) who criticized CBS for caricaturing Black Americans in offensive ways, which felt all the more gratuitous since the fifties were a time when Black people were struggling to achieve equality, plus the fact that it was the ONLY show on TV with Black lead characters almost made it propaganda for how Black Americans were to be viewed (in this case as clowns, crooks and, in the case of Black women, shrews).

Nonetheless the sole act of casting Black people in lead roles was a glass ceiling moment for Black television viewers. Some Black people praised the show for opening the door for Black actors while other Black people saw it as an offensive and rose-tinted depiction of the Black experience through the lens of White people. It would take a few more years before Norman Lear produced sitcoms like Good Times which showed Black people in more of a flattering light, but you can’t ignore the significance of Amos and Andy.

I Love Lucy (1951-57, CBS)

This was probably the most universally beloved sitcom in television history, but what many fans of I Love Lucy may not realize, especially today’s fans, is how groundbreaking the show was. Not only did Lucille Ball have creative control behind the scenes as the co-founder of Desilu Productions but the episode when Lucy becomes pregnant (although CBS prevented the cast from using the word “pregnant” in the actual show) was one of the most significant episodes in TV history. The 1947 television sitcom Mary Kay and Johnny depicted a pregnant woman earlier, but I Love Lucy was the first to center an entire plot on pregnancy. Ball was actually pregnant in real life and she and Desi Arnaz chose to incorporate the event into the show to much publicity (the year Ball gave birth, 1953, was the same year that TV viewers were introduced to “Little Ricky.”) It was so taboo at the time that the pregnancy episode almost got banned, but it succeeded at normalizing a natural part of human life that had never been seen on screen by TV viewers before.

That Girl (1966-71, ABC)

The significance of That Girl was its depiction of a lead female character. Ann Marie (played by Marlo Thomas) was the first independent career-focused woman on television. She had a boyfriend, but even that was depicted in a groundbreaking way because while she had a man in her life, her man was not the center of her life. A far cry from the portrayal of women in previous sitcoms, even the more revolutionary ones like I Love Lucy and The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Julia (1968-71, NBC)

Starring Diahann Carroll as Julia Baker, a Black woman who worked as a nurse and raised her son by herself after her husband died in Vietnam, Julia was undoubtedly groundbreaking in its depiction of a Black woman. The bad news is that many Black viewers found it to be sanitized and unrealistic. How fair this criticism was is up for debate though. The reason why I say that is because, whether it deserves the criticism or not, shows that break ground in their representation of minorities always get scrutinized. Not just by people who favor diversity but obviously also by racists. In this case, the more you satisfy one group of viewers the more you disappoint another, because it was being scrutinized by both conservative White viewers and Black viewers who craved authenticity. This was still 1968 and the tug of war between racial justice organizations expressing concerns over the show’s depiction of Julia and NBC rejecting Carroll’s request to wear her hair in an afro (the show was either too Black or not Black enough) was ultimately too much pressure for Diahann Carroll and she quit the show for her own well being. Although the show was popular while it lasted and it deserves credit for showing America that it’s possible for a Black woman to lead a successful series.

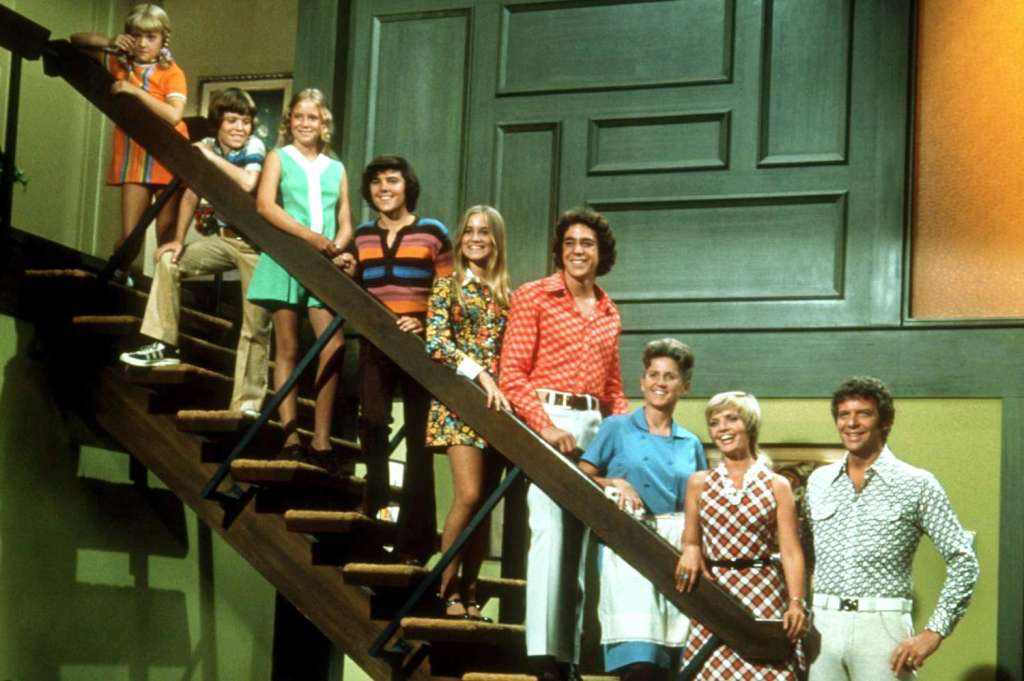

The Brady Bunch (1969-74, ABC)

This may be a strange show to include on this list but I want to give credit where credit is due. Yes this sitcom was so saccharine and rose-tinted that even The Brady Bunch Movie couldn’t help but acknowledge that fact in a satirical way, but putting aside my personal feelings about the show’s quality, a TV series about a mother with three daughters who meets a man with three sons and get together as one big step family was definitely not a traditional sitcom set-up in the sixties. Thankfully it had enough going for it that the gimmick is not the main thing people remember about it, and that’s a good thing because it means the writers were doing a decent enough job. Plus even my cynicism is not immune to that absolute banger of a theme song.

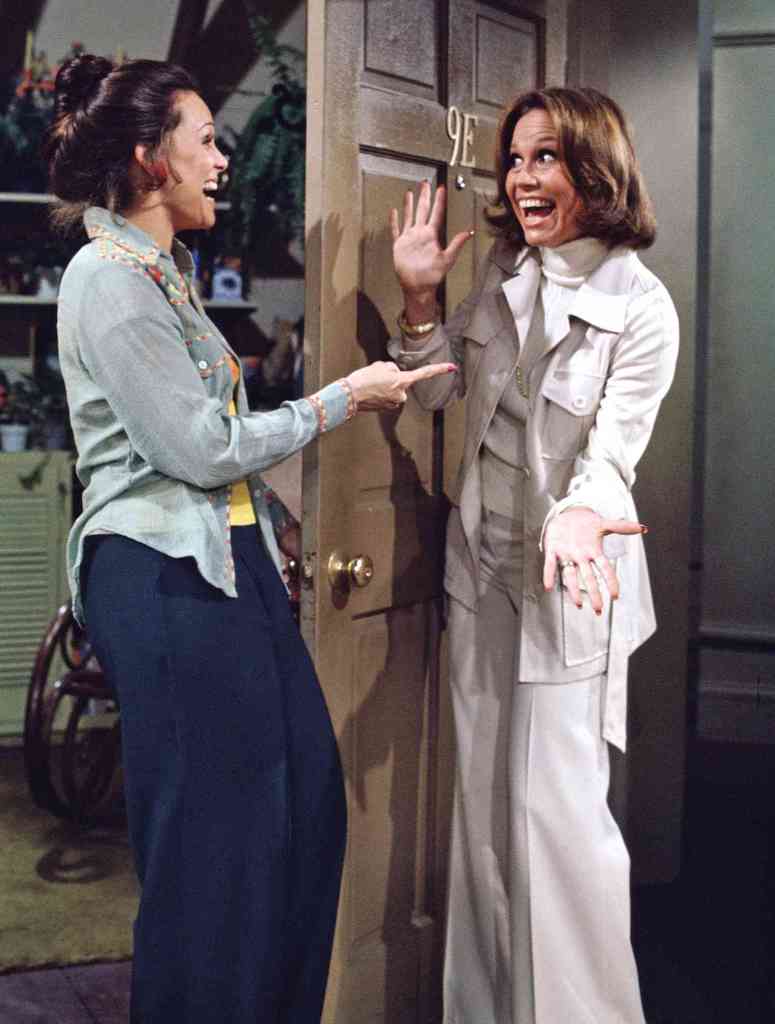

The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-77, CBS)

While That Girl and Julia both portrayed independent women in lead roles, The Mary Tyler Moore Show was by far the most radical. The character Mary Richards was not only single but her backstory is that she broke off her engagement to move to Minneapolis for a job opportunity at The Six O’Clock News. Which means she literally chooses a career over a man in the first episode.

All in the Family came out a year after The Mary Tyler Moore Show so the comedy was obviously not as hard-hitting as a Norman Lear script, but the fact that it was treating Mary’s story like it was normal in a normal sitcom way was itself pretty radical. Although it wasn’t just the feminist plot that felt original. Unlike a show such as The Honeymooners where each episode told its own self-contained story, Mary Tyler Moore really treated its cast of characters like real people who evolved, changed and underwent dramatic life events that carried over from episode to episode. I Love Lucy did this to an extent with the pregnancy storyline but Mary Tyler Moore took it to a much deeper level. Not to mention, just like All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show used humor to explore previously uncharted sitcom topics such as sex, adoption, beauty standards and the male ego.

You get the idea. The seventies were a watershed moment for sitcoms in a lot of ways. And in my next article, which will be titled “Sitcoms After Norman Lear,” I’ll discuss some of the shows that came out in the aftermath of this new age of TV comedy.