In film, a montage is a series of scenes edited together that is meant to convey an overall message, sometimes combined with fades, dissolves, split screens, double exposure and music and without audible dialogue, usually because it pushes the story forward more effectively than one scene is able to. It is a very common device that we see used all the time now in films around the world, but it actually has its origin in the Soviet Union. Of course Soviet montage started out as something very different from the modern montage most people are familiar with.

At the end of the 19th century when cinema was essentially invented, Russia would not officially enter the film industry until 1907, and even then, Russian films were made strictly for domestic distribution with very few released overseas, although we now know that the Russian films of that period included melodramas, horror films and costume dramas just like the films of Europe and America. However, once the political and social change of the Russian Revolution took place in 1917, an event that led to the dissolution of the Russian Empire and the formation of the Soviet Union, that country’s politicians began seeing the value of film as a tool for propaganda, so the Russian film industry, albeit under heavy scrutiny from Soviet leaders, began to flourish.

It was in this post-war period that Soviet filmmakers would begin experimenting with film narration. This was around the same time Germany was experimenting with expressionism, but while German filmmakers concentrated on using expressionism to convey feelings through the look and feel of an individual shot, Soviet filmmakers concentrated on the conveying of feelings through joining individual shots together. Although fun fact: montage was actually born out of necessity as well as creativity.

In the aftermath of World War I, most of Europe was in the middle of a film stock famine, and Russia’s was one of the most severe, so the filmmakers there looked for ways to tell stories on screen with the few resources they had, and one of those ways was telling stories with a series of shots rather than long takes. Take the newsreel director Dziga Vertov for example. Vertov could only shoot with small scraps of film stock, so when he documented scenes of post-war Russian life (edited by his wife Elizoveta Svilova), he made every shot count with dynamic cinematography that conveyed information and emotion to the public in the most direct way possible. Vertov would go on to become more famous for his 1929 documentary The Man with a Movie Camera, a brilliant movie within a movie that exposed the tricks of editing while simultaneously implementing them in entertaining ways.

Because of the scarcity of film stock, even the Moscow Film School relegated students to experimenting with drafting scenarios and editing pieces of film that already existed, including films that were imported from the West. One of those films was D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), which was not only a groundbreaking film in America but it heavily influenced the film students of Moscow, who admired it for its bold cutting and the way Griffith used editing to drive the narrative not only to convey messages but to intensify emotion. This was because many Russians saw editing as the basis of film art.

Lev Kuleshov, who established his own workshop at the Moscow Film School, is seen by many as the father of modern Russian cinema, with his influential experimentations in editing, including the way he used what he called “the artificial landscape” to do things like make it look like a man who is standing in the streets of Moscow can point at the White House in Washington D.C., just by editing two shots together. Of course D.W. Griffith was a filmmaker who also liked to build artificial landscapes, which may have been where Kuleshov got the idea. But Kuleshov taught Russian filmmakers that editing can serve a narrative function that can allow the audience to focus on the most psychologically significant aspects of a film. Not just by cutting to something that a character is pointing at but by cutting to a flashback or by cross-cutting. As well as generating an intellectual response from the audience, such as when Sergei Eisenstein cuts away from a group of workers to the slaughter of an ox, to convey that the workers have just been slaughtered by soldiers in the film Strike (1925).

There’s also the contrast cut, which Griffith demonstrated when he cut from a rich man’s gluttony at a dinner table to a bread line for poor people in A Corner in Wheat (1909). And then there’s the use of fast cuts to intensify emotion or slower cuts to linger on an emotion. Soviet directors put a lot of value in the narrative, intellectual and emotional usage of editing, and the Soviets decided to name this editing technique “montage.” The word “montage” literally means “editing” in France. But for Soviet directors and theorists it signified a certain dynamic type of editing that was important to the film’s overall structure. Although that didn’t mean that every filmmaker in the Soviet Union agreed on how to use montage.

Sergei Eisenstein is widely considered the greatest Soviet filmmaker to apply the principles of Kuleshov. Eisenstein was a master director and editor who was able to use montage, rhythm and his own understanding of emotion to tell powerful stories, often not with a singular focus on individual characters or personalities but with a focus on the film’s themes, although his films are far from devoid of humanity. From his first film Strike, Eisenstein was demonstrating a brilliant boldness with his directing style, including the way he used the contrast of the lives of poor people with the lives of rich people to highlight the injustices of classism, as well as the way he depicted Czarist capitalism as inhumane.

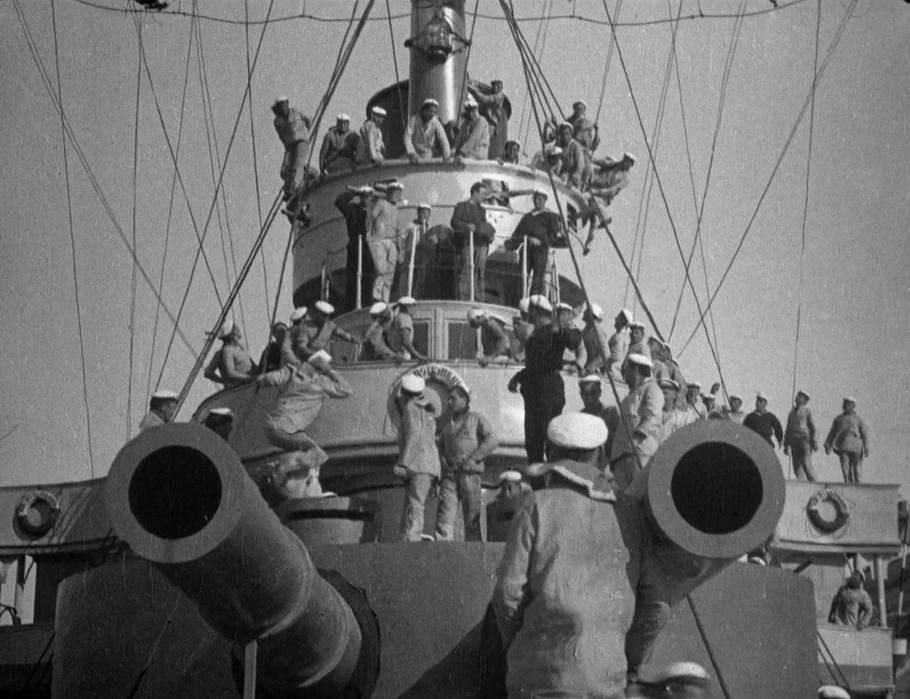

Similarly brilliant was Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) and the way it depicted a workers’ revolt in several parts, starting with the sailors’ discontent with the maggot-infested food they are being ordered to eat and leading to the escape to shore and the threat of retaliation from the fleet of battleships. Examples of editing being used to enhance the drama can be seen all over this film. None more so than the scene in which soldiers fire at innocent civilians on the Odessa Steps as retaliation against the revolting sailors, which effectively showcases the brutality and horror of that moment. This is the quintessential example of a film whose editing is used so well that you barely notice it because you are so engaged in the story.

One Soviet director who used montage differently from Sergei Eisenstein was Vsevolod Pudovkin. Pudovkin was a filmmaker who liked to use montage as a way to link together his themes, but while Eisenstein liked to up the tension and excitement in his films, Pudovkin’s films are more warm and relaxed, sometimes even using natural imagery to convey emotion, and also unlike Eisenstein, Pudovkin liked to focus on individual protagonists rather than a collective group of revolutionaries, and Pudovkin was also more focused on emotion than commentary.

An early example of Pudovkin’s ingenious use of editing was his 1925 short comedy Chess Fever, which, unlike the comedies of America, was more of a comedy in editing than in action, such as the way Pudovkin makes us think two people are playing chess at the beginning of the film before we zoom out to reveal a single man playing chess with himself, and Pudovkin’s use of continuity in the editing for this film is also brilliant. But Pudovkin’s film Mother (1926) showcased his ability at its height with the way he told a human story that used montage to reinforce human values and enhance the drama, including the way he understates his direction to make a scene feel more still in order to linger on the sadness and make a heartbreaking scene even more heartbreaking, and the way he juxtaposes scenes of evil with scenes of joy to emphasize the evil. Pudovkin was also great at using camera angles to convey feelings, such as when he used high angles to show how small and helpless his characters feel. Something he did in Mother as well as at the end of St. Petersburg (1927).

There are plenty of other Soviet filmmakers I could talk about besides Eisenstein and Pudovkin who used montage in brilliant ways, such as Alexander Dovzhenko who used montage in Arsenal (1929) when he used a scene showing a train car full of Czar soldiers crashing as a metaphor for the dangers of blind allegiance to a tyrannical government. But this is an article about a film technique, not any one film director. Although I will say that as Joseph Stalin grew in power in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, so too did the suppression of artistic expression in many Russian films (a common theme in countries led by fascists as German and Italian filmmakers well know), which gave way to more realist films and Soviet propaganda, so as innovative as all the films I just mentioned are, it was only after Stalin’s death in 1953 when Russian films became more personal and therefore more powerful. But that did not stop the Soviet technique of montage from being adopted internationally. In fact Hollywood admired Eisenstein so much that they started using metronomes while cutting their films to edit them more like Eisenstein.

But while some American films used montage the Soviet way, such as in the movie Psycho when Alfred Hitchcock showed Janet Leigh getting stabbed to death in the shower not in one long shot but in multiple close-up shots, much more common was the “Hollywood montage.” The training montage in the Rocky films is a popular example of how most American films used this technique, and this type of montage has been used so much that it almost feels like it has been satirized just as much. Although that kind of montage can still be used to emotional effect, even in American films like Pixar’s Up. Like all film techniques, they are only as powerful as the filmmakers who use them.