Animator Marc Davis was a star at the Disney studio from the 1940s to the 1970s and while Walt Disney never overtly played favorites, you could definitely tell he was one of the artists who Walt valued the most, and for good reason.

Marc Davis was born in Bakersfield, California in 1913 and was basically a self-taught artist since childhood, often sketching the animals at his local zoo while at the same time observing human beings and drawing them too. His keen observation of living things and the ways they behaved would be a key component in his development as an animator, and he had a lot of time for practice since his parents were often busy and he moved around a lot because of his father’s constantly changing jobs. A lonely life for a child. But when he got older he attended art classes wherever he could, including the Kansas City Art Institute where Walt Disney happened to study, and the Otis Art Institute (now known as Otis College of Art) in L.A., a school which featured such alumni as Looney Tunes director Bob Clampett and Bambi background painter Tyrus Wong. And Davis also managed to get his cartoons into a few newspapers.

A fan of Disney cartoons, especially Silly Symphonies like Three Little Pigs and Who Killed Cock Robin?, a theater owner friend suggested to Marc Davis that he apply to work at Disney. Following the death of his father, Davis soon needed to become the sole breadwinner in his Great Depression-era family, so he did eventually apply to Disney and thankfully his animal sketches were impressive enough that he got hired on the spot.

Marc Davis was hired by Disney in 1935, the same exact year he left the theater after watching Who Killed Cock Robin? Milt Kahl was another young star animator at the time who befriended Davis quickly because the two respected each other’s talents and they were both more worldly in their art experience than many of the other trainees at the time who came from the world of newspaper cartoons.

Marc Davis became an assistant animator on Disney’s first animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), assisting Grim Natwick with his animation of Snow White (while Milt Kahl ironically handled animating the forest animals), although Davis did marvelous work cleaning up Natwick’s rough animation. But the first time Davis really got Walt Disney’s attention was when Walt saw Davis’s story sketches for Bambi (1942). The Disney artists were having a bit of trouble developing the art style for Bambi in pre-production but Davis would be a key player in cracking the code, because while most of Disney’s artists were drawing anatomically correct wildlife, Davis’s design for Flower the skunk stood out as appealingly human-like in his expressions, and Walt Disney pointed to Davis’s drawings of Flower as the key to the picture.

As a result of Davis’s artistic influence, Bambi, Thumper, Flower and all the other characters all moved like animals but behaved and emoted like humans. Davis once explained that it was all about balancing their animal qualities with their human qualities. Walt agreed with this approach and he wanted Davis’s drawings translated to the screen so badly that he ordered Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas to teach Davis how to animate. Although Grim Natwick had taught Davis a lot already so he was halfway there. Davis would soon become the master of animating characters who are meant to be cute and appealing, and following in the footsteps of Natwick, who was hired by Disney to animate Snow White based on the strength of his Betty Boop animation, Davis would later become a primary go-to animator of Disney women and girls, which I will get to shortly.

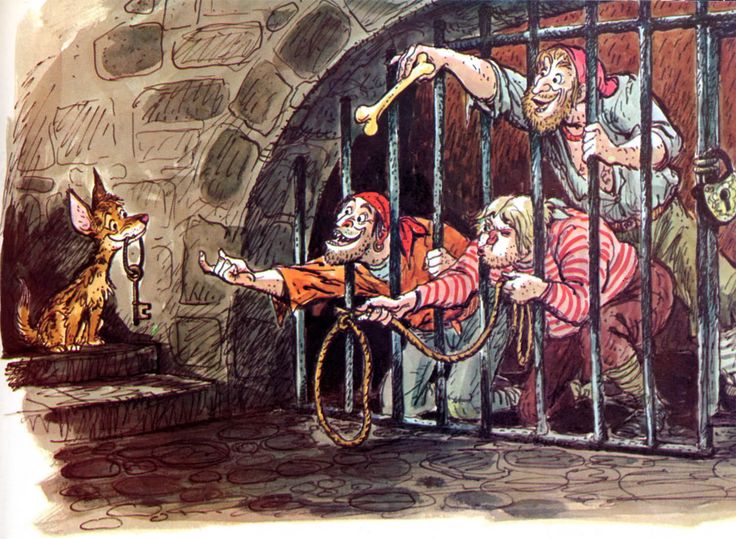

In Bambi, Davis animated the scene of Flower falling in love with a female skunk, and when Davis heard the sound of the audience’s laughter during that scene, he officially fell in love with working in the medium of animation, although he continued to do concept art. And even though his screen credit was sometimes confusing in this period (he requested to be credited as M. Fraser Davis on Bambi but instead he was listed as Fraser Davis), and sometimes his credit on a film was completely absent even when he worked on it extensively (like in the 1943 war propaganda film Victory Through Air Power for which he drafted much of the battle between the eagle and the octopus), Davis still received a lot of respect behind the scenes. And the name “Marc Davis” finally appeared on screen for the first time in Song of the South (1946), for which he animated much of Brer Fox and Brer Bear in the Tar Baby sequence and contributed story sketches for Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit’s live-action/animated interactions.

Davis also animated many of the characters from the Wind in the Willows segment of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), and around this time in 1947, Disney’s art instructor even asked Davis to take over as the teacher of the advanced drawing class at Chouinard Art Institute (now known as CalArts) so Davis had a side gig doing that for the next seventeen years as well, sometimes lecturing up to a hundred students at a time.

Marc Davis became a directing animator in the fifties, kicking off a decade in which Davis would handle many of the leading ladies of Disney’s animated features, including Cinderella, Alice from Alice in Wonderland, Wendy from Peter Pan and Aurora aka Briar Rose from Sleeping Beauty. And while realistic humans were not the most fun assignments, Davis put all his creativity and drawing talent into bringing them to life. One of his biggest career highlights was animating the scene when Cinderella’s tattered dress transforms into a ball gown, which Walt Disney once said was his favorite piece of animation.

Davis also animated the vain, jealous and hot-tempered Tinker Bell in Peter Pan, and while she certainly tested your willingness to excuse a character’s behavior, Davis animated her with clear affection and his love for the feisty fairy shines through with animation that gave her femininity, a lot of spunk and most important of all a strong personality.

Maleficent, the evil fairy from Sleeping Beauty, was more of a challenge to animate because she was supposed to be regal, still and subdued in her emotions. Although Davis helped design the character, inventing her flame inspired costume design which was inspired by actual medieval art.

But Marc Davis’s biggest tour de force as an animator and his final animation assignment at Disney would be on Cruella de Vil, the villainess from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) who Marc Davis animated single-handedly in every shot she appeared in. Unlike Maleficent, Cruella was bigger in personality and more likely to interact with those around her physically, therefore making her much easier and more fun to animate. Bill Peet’s excellent storyboards and Betty Lou Gerson’s excellent vocalization guided the animation heavily, but Marc Davis added a lot with his personal touches, and as a result, Cruella ended up becoming one of the biggest scene stealers in that film and one of Disney’s most memorable and popular villains.

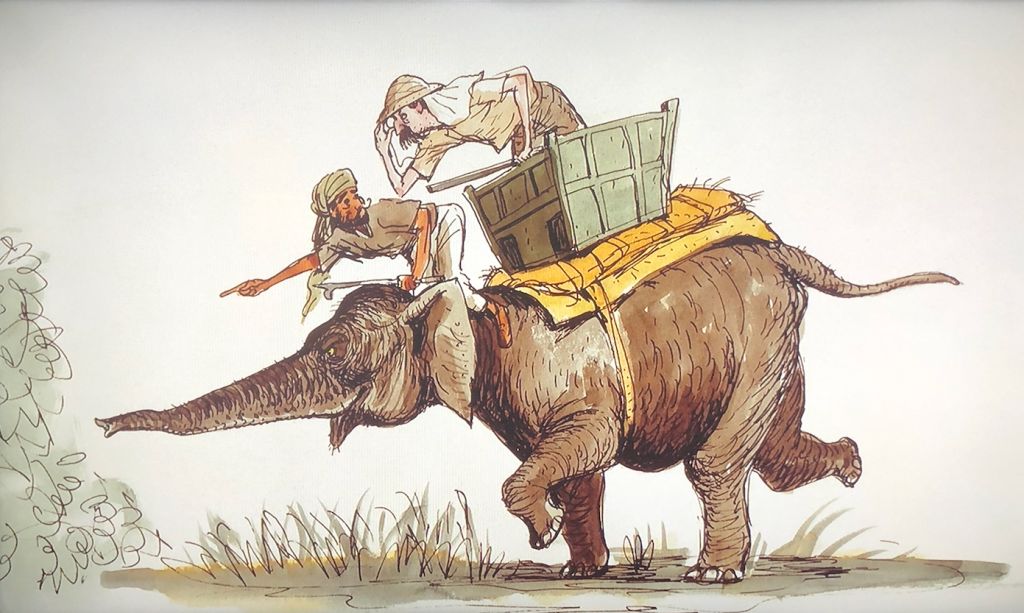

In 1962, a year after One Hundred and One Dalmatians came out when animation assignments were more scarce and some of Disney’s artists had free time, Walt Disney asked for Marc Davis’s help evaluating what worked and what didn’t work about a concept for a Disneyland theme park attraction called Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland, a ride attraction where park visitors would go on a journey through the wilderness with over 200 animatronic critters in sight. Walt was dissatisfied with it and wanted Davis’s critical artistic insight, so Davis came up with gags that livened up the behavior of the animals in the attraction, and when he showed Walt his concept art, Walt invited Davis into the Imagineer meeting to explain his ideas. In fact, Walt liked Davis’s ideas so much that he assigned Davis to work on the concepts for other attractions, including the Carousel of Progress, It’s a Small World and Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, which all made their public debut at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

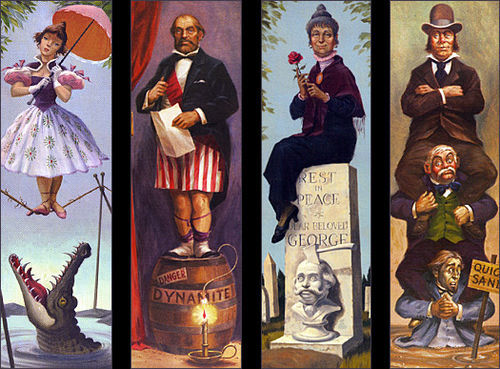

Marc Davis later came up with many of the gags, dialogue, characters, costumes and more for the Pirates of the Caribbean ride, as well as the Haunted Mansion for which he did a good job balancing spookiness with fun, with such ideas as the stretching portraits that elongate as you ride the elevator to the basement as well as those hitchhiking ghosts. Davis also worked on the Enchanted Tiki Room, the Jungle Cruise and the Country Bear Jamboree, the latter being the last concept he showed Walt personally before Walt Died in December of 1966. Thankfully Walt found Davis’s art hysterical and gave his thumbs up to the Country Bears.

Davis continued creating concept art for the Imagineers until his retirement in 1978, but he still loved to draw long after he left Disney, and he still attended Disney events and interacted enthusiastically with young animation fans in his retirement years. Even the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences saluted his career in 1992, while that same decade he fulfilled a lifelong dream: having his own art exhibit featuring paintings by Davis himself. He later died in 2000 at the age of 86.

Marc Davis’s artwork at Disney was filled with humanity and superb draftsmanship that made it unique among his peers. He was not only a brilliant animator but a brilliant designer and storyteller. Walt Disney recognized this and saw Davis as his Renaissance man. A man who could pull off whatever Walt demanded of him. A clear sign of Davis’s talent was when Milt Kahl, one of Disney’s most talented and well-respected animators with the biggest ego of them all, acknowledged that while Davis and he were assigned the most difficult animation assignments (especially when Walt gave them the realistic humans), he had to admit that he thought Davis was the superior draftsman. Plus not many animators influenced both Disney’s most popular films and Disney’s most popular theme park attractions in such a direct way, which truly makes him an outstanding person in the studio’s history.