The perception of video games from a toy for kids to a sophisticated piece of art that adults could appreciate was bolstered in large part by the PC market. In the eighties when arcade games reached peak popularity and companies like Atari and Nintendo were largely targeting juvenile audiences, most Apple and Microsoft users were older, so computer games were naturally a better fit for mature content. A good example of this was a game whose creators were traversing such unexplored territory in interactive entertainment that they weren’t actually targeting any audience but themselves, and that game was Myst.

Myst is basically a point-and-click graphic adventure game designed by two brothers named Rand and Robyn Miller and initially released on the Mac. The game takes place on an island called Myst where solving certain puzzles will allow you to travel to different worlds via interaction with various objects across various locations.

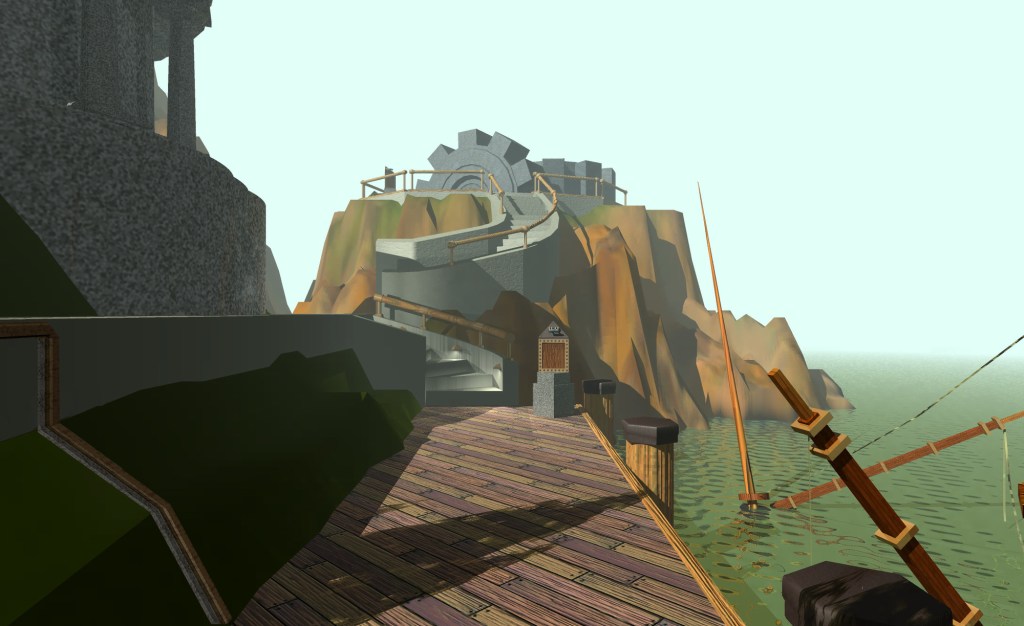

Played in the first-person with progression achieved through the pointing, clicking and dragging of a mouse, the object of the game is basically to explore the island of Myst as thoroughly as possible in order to discover and follow clues while using books to transport to several “Ages,” which include the Selenitic Age, Stoneship Age, Mechanical Age and Channelwood Age, each containing their own puzzles to solve. But a unique aspect of the exploration-heavy game is that it guides you very little, not even providing much backstory for why you are even on this island in the first place nor any obvious objectives, enemies or real sense of danger. But this just adds to its uniqueness and its mysterious atmosphere.

There actually is a plot, and it’s a pretty interesting one involving books with missing pages that hold secrets of a family who lived on Myst but suffered a tragedy. The more missing pages you collect, the more you learn about this family and the more clear the story becomes, and depending on your actions, there are multiple paths for how the story might end.

The creators of Myst, Rand and Robyn Miller, were not really gamers, other than the occasional session of Dungeons & Dragons and Zork, but Rand had computer programming experience and Robyn had imaginative world-building and storytelling skills, and Rand approached Robyn with the idea of going into interactive entertainment. This led to the founding of their software development company Cyan, Inc. (now known as Cyan Worlds) and the creation of a few games aimed at children such as The Manhole (1988), Cosmic Osmo (1989) and Spelunx (1991), which like Myst were point-and-click world exploration games viewed in the first person, albeit with stories that were nowhere near as deep as Myst‘s narrative, for what little story those games had.

In 1990, once the Millers had the idea to change things up and make a game that would appeal more to adults, development on Myst would begin a year later. With the goal being to create a game that would stimulate the intellect of its players and force them to make ethical choices, all in a non-linear story inspired by authors like C.S. Lewis and Jules Verne combined with the deep mythology of a Star Wars movie, involving a mystery the player must solve and characters who were grounded in believability.

Myst was also a graphical departure from Cyan’s previous games with the HyperCard software of Apple’s Macintosh computers allowing not only for color but for 3D rendering, which made the idea of building a fictional world a lot easier for the game developers. The vast environment of the game, from indoor settings to outdoor settings, also guided the development of the puzzles players must solve.

The game even featured a few live-action cinematics, and while the limitations of CD-ROM space proved a challenge for the Cyan team, they worked around this in creative ways, lowering the kilobyte space wherever possible and subtracting nothing from the experience.

Activision worked with Cyan before on their games aimed at kids but they initially passed on publishing this. So did Sunsoft who was only interested in publishing games for consoles and not PCs, but the Millers eventually got Broderbund on board for Mac publication and once Myst hit the market in 1993, it became a huge incentive for people to buy CD-ROMs alongside Trilobite’s puzzle adventure game The 7th Guest, exceeding the Millers’ sale hopes by double in just six months after its release, reaching quintuple by year’s end and becoming the highest-selling PC game of all time until 2002 when it was surpassed by The Sims. And Myst was not only a huge commercial success but a critically acclaimed one, with many critics appreciating the way it differentiated from other CD-ROM games on the market as well as its stunning graphics and effective sense of actual world exploration. Publications like the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle even pointed to Myst as a sign of the video game medium’s evolution from toy to art.

Just like most groundbreaking works of art, it had some detractors. Some of the modern-day criticism is fair (or unfair depending on how you look at it) because the interactive slideshow feel of the exploration mechanics are primitive to today’s standards, but even in the nineties when the game’s commercial success was at its peak some critics found it baffling, too vague to be enticing and too difficult to solve, with reactions pretty split down the middle on the story even while many still thought the game’s presentation was nice. But no one could deny how innovative it was.

The game was even more successful once Cyan ported it from the Mac to Microsoft Windows, and it later received ports for Sega Saturn, PlayStation, Atari Jaguar, AmigaOS, CD-i and 3DO. And it led to sequels that were also positively received, including Riven (1997), Myst III: Exile (2001) which Cyan allowed Presto Studios to develop, Ubisoft’s Myst IV: Revelation (2004) and Myst V: End of Ages (2005) which was developed once again by Cyan. Plus the Millers collaborated with sci-fi author David Wingrove on novels which expanded the universe of the game, with the three novels subtitled The Book of Atrus, The Book of Ti’ana and The Book of D’ni and published by Hyperion. Myst has also been approached by film and TV studios for adaptations, and even Disney had the idea to adapt the game into a theme park, but none of this has come to fruition. Although a film by Village Road Show is currently in the works as of this writing.

Although Myst inspired many copycats that almost oversaturated the genre, and some traditional gamers derided its influence on the medium and the proliferation of casual games, Myst‘s creative approach ultimately proved to be a good thing for the medium and the market. It inspired game developers around the world and gave them new ideas for how to approach games, breaking from the idea that every game needed a hero vs. villain story or a limited number of chances that forced you to start the game over once you ran out of lives. Obviously this was still very much the norm. After all, the shooter game Doom came out the same year as Myst and was also highly popular, but Myst helped initiate a more ambitious arthouse approach to video games which could be seen in the years and decades after. Especially in the world of PC games.