I previously wrote about Walt Disney’s venture into television production and how the Disney company successfully made the leap from the big screen to the small screen, but there was one man I didn’t mention who was largely responsible for that leap and that’s writer and producer Bill Walsh.

Born in New York City in 1913 and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, Bill Walsh was a football player turned sports writer for the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune who later enrolled in the University of Cincinnati in the 1930s. As a freshman at UC he produced his own local show and was discovered by the actors Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay while they were passing through town to perform the musical Tattle Tales, and apparently young Walsh made an impression on them because they hired him to rewrite their play, which paved the way for Walsh’s entry into Hollywood where he became a writer and a press agent.

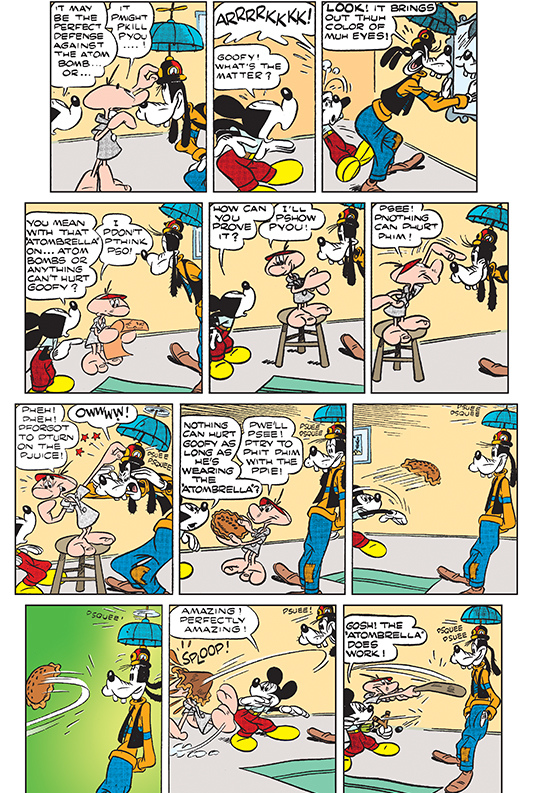

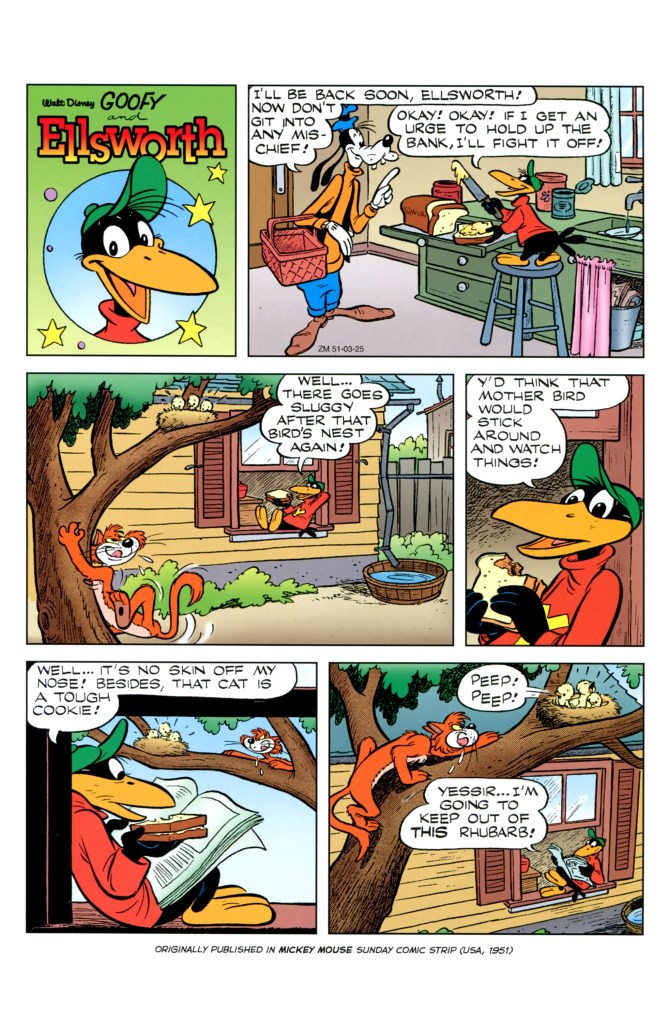

Walsh initially joined Disney in 1943 as a press agent, but he also wrote Mickey Mouse comic strips for Disney on the side with renowned Mickey cartoonist Floyd Gottfredson. Although Walsh was probably jealous of Carl Barks because he reportedly thought Donald Duck was a better character than the more straight laced Mickey (most audiences in the 1940s agreed). But Walsh’s interest in more exciting characters translated to a penchant for exciting writing, and he created comics for Disney that leaned more into sci-fi, mystery and horror than ever before. He even created a few characters for the Mickey Mouse comics, like the time-travelling Eega Beeva who became a frequent sidekick of Mickey’s and a main protagonist in the late 1940s, as well as Ellsworth the myna bird who started out as Goofy’s pet and later became more humanized as another one of Mickey’s frequent sidekicks in the Sunday strips. Although it underwent format changes through the years, Walsh wrote these comics until 1964, with Roy Williams taking over afterward.

Another significant thing that happened in the late forties was Walt Disney’s decision to put Walsh in charge of their television operations, beginning with Disney’s first TV production the NBC Christmas special One Hour in Wonderland (1950) which was a huge success that paved the way for Disney’s entry into weekly television production.

Walsh went on to produce the Davy Crockett segments for that anthology series as well as The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-59) and its various serials that aired within the show like Spin and Marty, The Hardy Boys, Adventure in Dairyland (starring Spin and Marty‘s Sammy Og, Mouseketeer Annette Funicello and young Kevin Corcoran in his Disney debut) and of course Annette, which starred Funicello as a poor country orphan who moves to the city with her upper-class uncle and aunt.

By the end of the decade, Walsh moved into feature film production, where he wrote and produced the wacky comedy The Shaggy Dog (1959) starring Fred MacMurray, Tommy Kirk and Kevin Corcoran. The film had a low budget but it was a huge hit, making it Disney’s most profitable film at the time. Walsh would go on to have more success working with MacMurray and Kirk in The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Bon Voyage! (1962) and Son of Flubber (1963).

Walsh also produced the film Toby Tyler (1960) starring Corcoran, he provided the story for sci-fi comedy The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (1964) starring Kirk and Funicello, and he wrote and produced a string of Disney films from the sixties to the seventies, including the highly successful Mary Poppins (1964) which Walsh co-wrote with frequent collaborator Don DaGradi and which would become Disney’s first Best Picture Oscar nominee in history, followed by That Darn Cat! (1965), Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. (1966), Blackbeard’s Ghost (1968), The Love Bug (1968), Scandalous John (1971), Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), The World’s Greatest Athlete (1973), Herbie Rides Again (1974) and One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing (1975).

If you were to tell Walsh that these were not exactly the greatest Hollywood films ever made, he would agree with you. But he reveled in creating “schlock” aimed at young audiences and never had any desire to make important statements with his art. He also loved the freedom Disney gave him to be totally nutty with his film concepts, which luckily was totally in tune with Walt’s wishes and the Disney brand.

Bill Walsh worked at Disney right up until he died of a heart attack in 1975.