And the strike goes on …

As someone who follows the entertainment industry closely every year, we are living through frustrating times right now because while fans have never been more enthusiastic and have never craved new film and television like they do now, Hollywood CEOs just can’t help but be the killjoys that they are. Keep in mind that while I am looking forward to many of the films and shows that the studios are delaying and whose productions they are putting on hold amidst the strike, I will gladly wait months and months for those things to get made if it means writers, actors and whoever else will finally get paid fairly, because this is a situation that is much bigger and more dire than “Oh no, Deadpool 3 might get delayed.” And it has been building up for a while as streaming services have become more and more dominant in the media landscape.

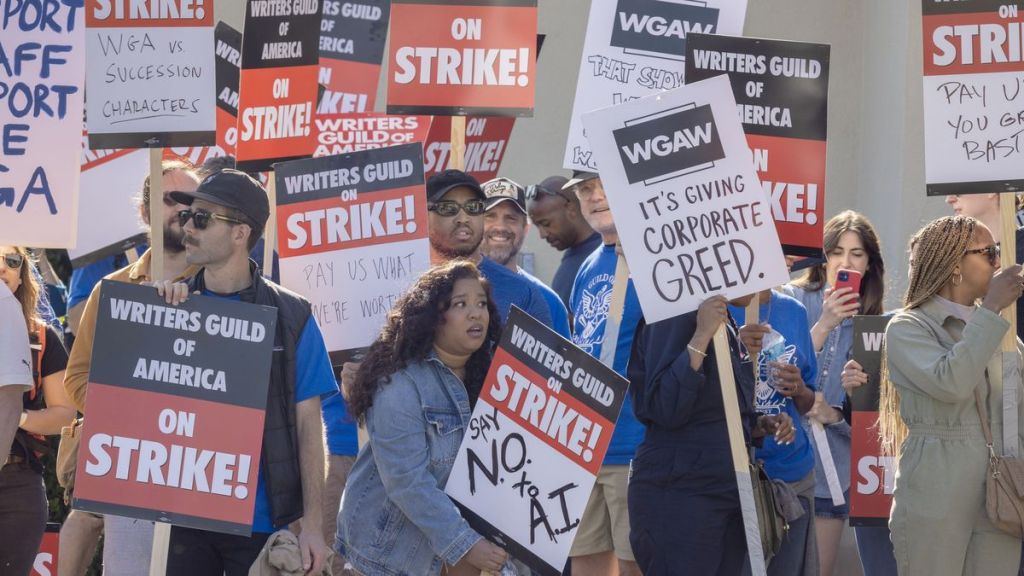

May 2, 2023 is when the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike for the fifth time in history since it was founded in 1951. The Guild, which has an East branch in New York City, a West branch in Los Angeles and in total represents 11,500 screenwriters, went on strike over a labor dispute with who else but the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) because it seems Hollywood producers still haven’t learned how to treat the people making the films and shows that make their companies so successful with the respect they deserve.

The AMPTP is an organization whose membership includes Disney, Warner Bros., Universal, Paramount, Sony, Lionsgate, Amazon, Netflix and Apple among others. It serves as the entertainment industry’s key bargaining liaison with the labor force behind much of the films and TV shows of America. A labor force represented not only by the WGA but by such organizations as the Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), the Directors Guild of America, the American Federation of Musicians, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and the Animation Guild.

Throughout the history of the WGA, the stubbornness of the AMPTP and their unwillingness to budge on any stance because of their apparent greed has always been the main reason why negotiations during strikes are so stagnant. During the first strike in 1960, the WGA’s main point of contention was the lack of compensation for writers over television broadcasts. In 1981 it was compensation from pay TV and home video. In 1988 it was residuals from reruns. In 2007 it was residuals from DVDs and new media. And now in 2023 it is residuals from streaming services, but this feels like more of an existential crisis than with previous strikes.

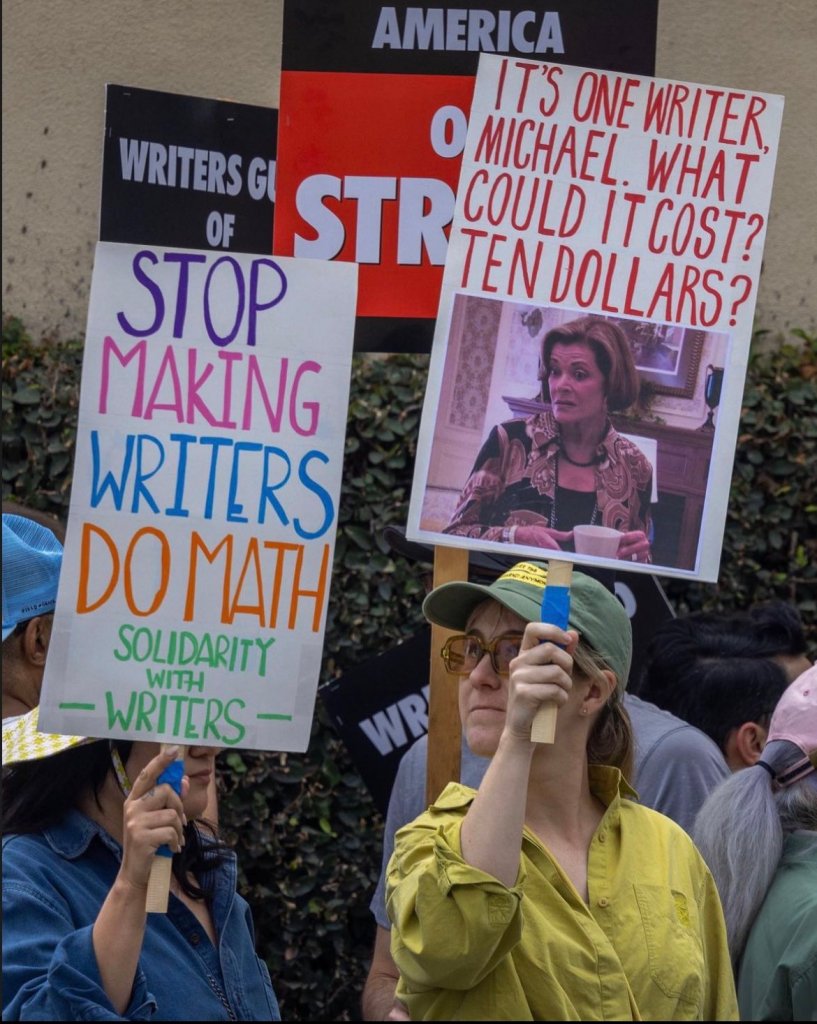

The amount of platforms available for distribution has actually gotten a lot bigger in the aftermath of the massive popularity of Netflix in the 2010s, but with that increase for opportunities comes a decrease in wages. According to the Associated Press, the amount of TV writers being paid minimum wage has increased from 33% to 49% in the past decade and residuals from streaming shows have been significantly cut down from the amount of residuals that writers received from television a decade ago. And the decrease of syndicated reruns is made even worse by the fact that streaming services are suspiciously tight-lipped about sharing viewership data with filmmakers, writers and the general public. So the creators behind shows like Stranger Things and The Mandalorian often don’t know exactly how profitable their own shows are. A clear example of how different the pay situation is for streaming is the amount of money talk show writers make working on shows like The Problem with Jon Stewart on Apple TV+ compared to the amount of money writers make doing the same amount of work on late night talk shows on traditional networks like The Late Show with Stephen Colbert on CBS. So upfront fees are a prime goal for the WGA.

Another issue is “mini rooms.” Which are writers’ rooms containing only a handful of writers. Something often deployed before shows are greenlit, so it’s possible for writers to work a year on a show that doesn’t end up getting picked up. The WGA wants requirements where writers feel less pinch and are prevented from being understaffed and overworked, but one would not be too far off to venture that studios have it in their heads that the less people they hire to work on a show, the less people they would have to pay.

Another big issue that the WGA wants to address? The fact that the practice of 22-episode broadcast seasons has become less common in the age of 10-episode seasons on streaming (sometimes less) has made it a lot tougher for writers who not only gain diminished returns but are held back by exclusivity terms should they have the desire to make extra money working on other shows.

And A.I. is one of the biggest points of contention. Many writers say the use of A.I. is fine but not if it’s going to be used as a tool for replacing writers. Safeguards around the use of A.I. are important not only for the WGA but for SAG-AFTRA as well.

And the WGA not only wants better residuals, increased pay, better staffing requirements, improved exclusivity deals and assurance on the use of A.I. but also practical things like pension plans and health care, both of which the AMPTP bafflingly rejected without a counterproposal.

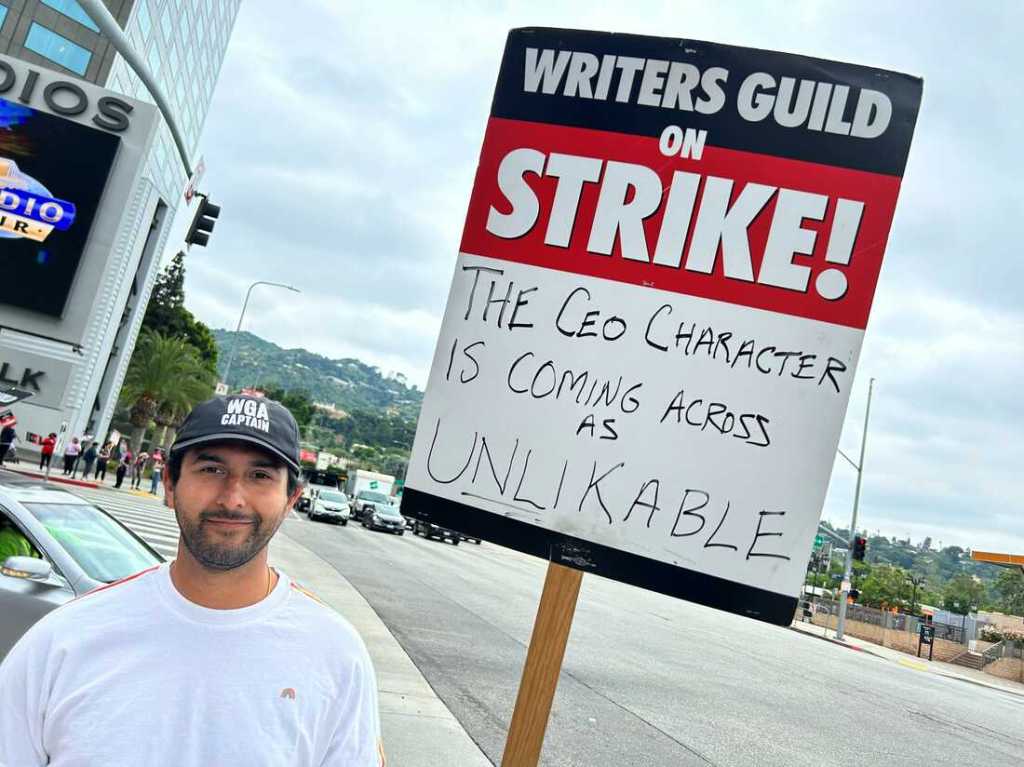

The response to all these things from the AMPTP has been the most baffling thing about all this. Take Disney CEO Bob Iger’s appearance on CNBC’s Squawk Box where he said that striking writers and actors (SAG-AFTRA went on strike in July, the first time since 1960 that American writers and actors went on strike at the same time) are being “unrealistic” about their demands, referring to business struggles in a post-COVID world, and he added that striking right now would be “disruptive” to the entertainment industry. Well, sorry workers didn’t go on strike at a more convenient time for you, Bob, but there’s something more important on the line here. Like the fact that you continue to exploit workers to chase a bottom line while caring surprisingly little about the livelihoods of those very workers.

Fact: if Disney agreed to the terms of the WGA, it would cost them about $75 million a year. The equivalent of half the budget of Strange World, a movie that made less than half of its budget back at the box office.

Also Iger conveniently avoided taking any responsibility for the strikes in that Squawk Box interview. That’s just one example of how shockingly arrogant, hostile and tone-deaf these CEOs can be. But on the bright side, the studios are pretty inept at garnering much sympathy in this situation. Not for lack of trying to control the narrative, but the WGA, SAG-AFTRA and many of their members have significant followings on social media too and many people trust their favorite film and TV stars more than they trust some guy named David Zaslav. Especially since a lot of people outside of show business can relate to working for greedy and exploitative corporations. As the LA Times says, “public support, brand loyalty, individual reputations, group unity, the fall TV lineup, the theatrical release calendar, film festivals and the Oscar race” are all stacked against the AMPTP right now, as well as the shareholders of those companies who might be curious to know when the studios that they invested their money in are going to allow their films and shows to go back into production and allow stars to promote them again. Many feel it’s only a matter of time before the AMPTP gives in to the demands of the Guilds. The CEOs are living in a fantasy land right now but for many people working in Hollywood this strike is a now-or-never situation that they seem determined not to budge on as well, because if the CEOs have their way, there won’t be a Hollywood to go back to because its foundation will have been destroyed.