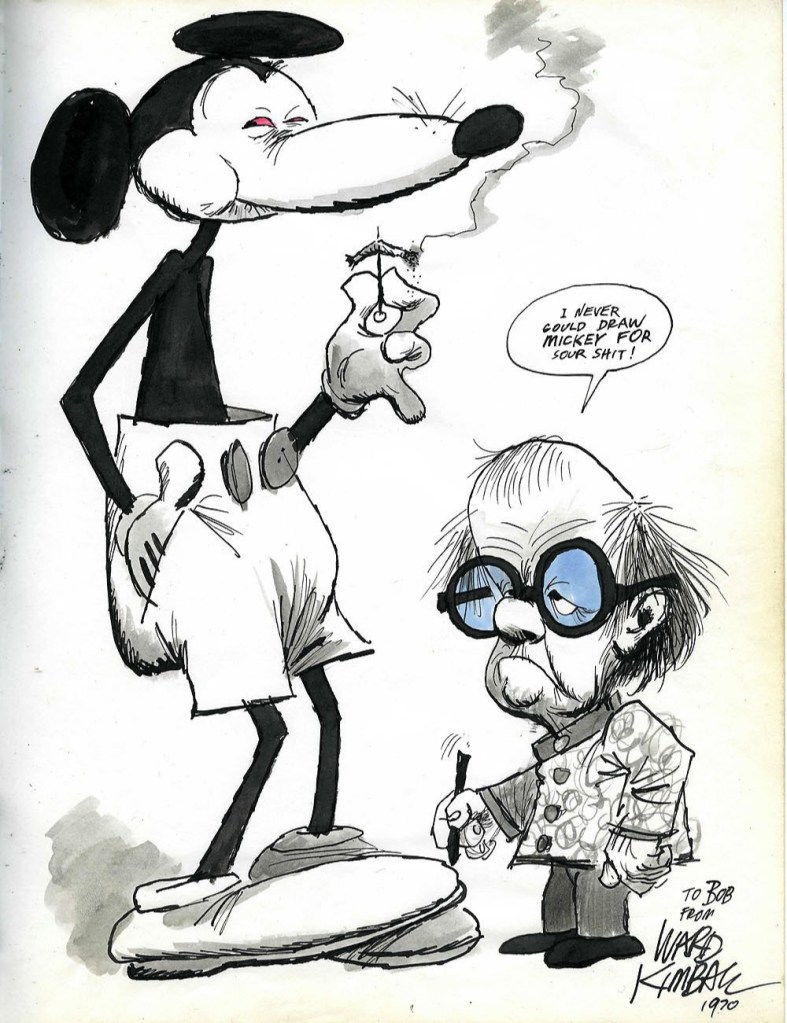

One doesn’t often think of wild and wacky animation when they hear the name “Disney,” but that’s exactly what Disney animator Ward Kimball was known for. And he was actually one of Walt Disney’s favorite animators, one of the few Disney employees who Walt had no problem calling a genius. Perhaps the most un-Disney-like of Disney’s Nine Old Men, Kimball’s stylized art and zippy timing would almost seem more at home at Warner Bros. or UPA. But he contributed to some of Disney’s most entertaining and memorable scenes and he himself was an entertaining person as well.

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1914, if you knew Ward Kimball’s mother you would know where he gets his quirky sense of humor as well as some of his talent. Several people in Kimball’s family were funny like him, although “pranksters” might be a more accurate description. Ward had been cartooning since he was a child and his father supported his passion for drawing so he enrolled Kimball in the W.L. Evans School of Drawing where Kimball received his first formal art training.

Ward Kimball was also a big vaudeville fan, which might have influenced his sense of humor as well. You can see where that might have come out in his animation, such as in the 1941 Mickey Mouse short The Nifty Nineties featuring caricatures of himself and fellow Disney animator Fred Moore performing on stage for Mickey and Minnie.

Ward Kimball was offered a scholarship at the Santa Barbara School of Arts and chose to go there over traditional college. He was originally interested in fine-art painting and illustration, but his exposure to Disney animation convinced him that Disney stood out from the rest of the animation studios which Kimball felt were too crude and unsophisticated. The Silly Symphonies in particular were what made Kimball realize Disney was creating true art. Three Little Pigs (1933) alone blew Kimball away as an ingenious work of caricature.

Kimball applied for Disney in 1934 bringing his art portfolio with him, which led to him getting hired on the spot, and he was to report to Disney animator Ben Sharpsteen a week later. Kimball worked as an in-betweener on two early Donald Duck shorts, The Wise Little Hen (1934) and Orphan’s Benefit (1934), and after six months Kimball was promoted to assistant animator under Hamilton Luske, much to the amazement of in-between supervisor George Drake who had wanted to fire Kimball for his anti-authority attitude and tendency to make fun of his co-workers (Ward Kimball had drawn a caricature of George Drake with Dumbo ears), but thankfully Kimball was talented enough that Hamilton Luske wanted to keep him. Kimball assisted Luske on The Tortoise and the Hare (1935), learning a lot from Luske about the art of caricature. And Kimball was a master observer, which helped him a lot with his caricature skills and therefore his comedy. Frank Thomas even said Kimball would have been a good political cartoonist because “he had everybody pegged.”

Ward Kimball’s first efforts as a solo animator were the insect dancers and jazz musicians in the Silly Symphony Woodland Café (1937), a hugely entertaining parody of 1930s New York café society. Kimball’s work here is perhaps what led to his work on Jiminy Cricket and later the dancing crows in Dumbo. Kimball also animated Cab Calloway in Mother Goose Goes Hollywood (1938). As Ward himself was a musician and a natural showman, he put a lot of himself into this animation.

By 1935, Walt Disney was shifting his focus away from the Silly Symphonies and more towards the development of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. By this time, Kimball had learned he was much happier being an animator than an illustrator. Animation was more of a challenge and it required a lot more patience and a lot more skills, including draftsman, analytic and actor. Walt Disney decided to put Kimball on Snow White, but it was a frustrating experience for Kimball because two scenes he fully animated (a soup eating sequence and a sequence where the Dwarfs make Snow White a bed) were deleted from the final film because Walt judged that they slowed down the film’s pacing. Although some Kimball animation remains, including the scene where the Dwarfs poke their noses over Snow White’s bed and the two vultures who follow around the queen in her hag form throughout the film.

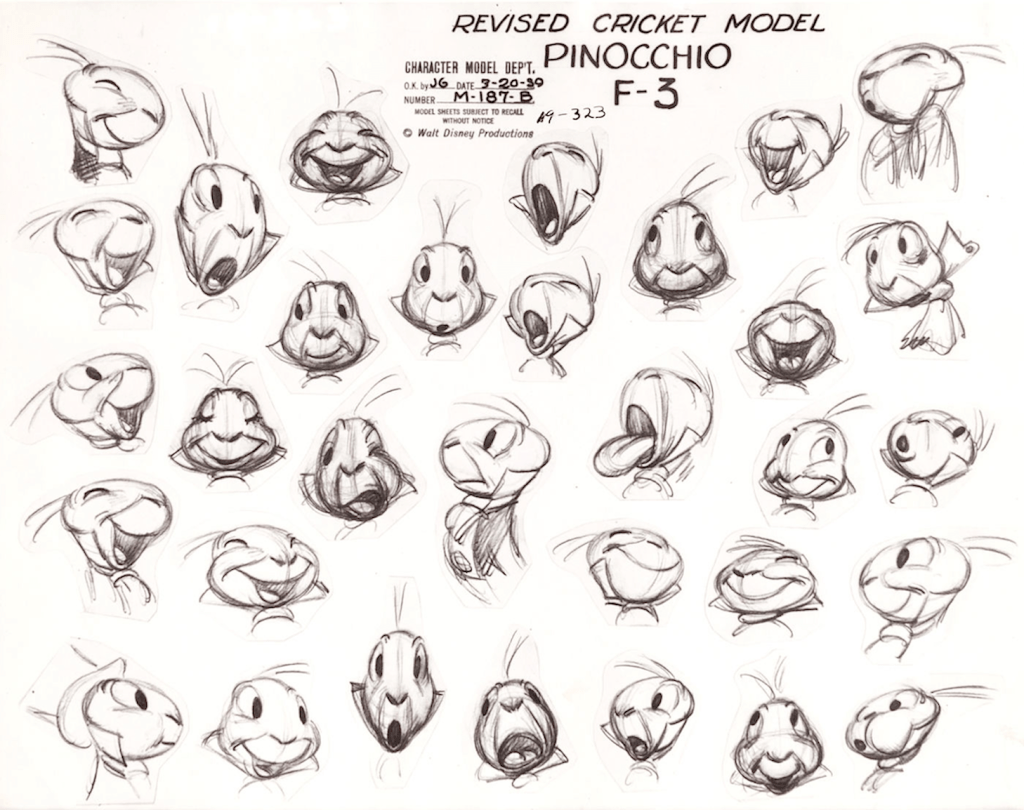

Kimball almost quit Disney because of this, but Walt made it up to Kimball by giving him the job of animating one of the main characters in Disney’s second feature film Pinocchio (1940), Jiminy Cricket. Kimball recalled that Walt was such a great storyteller that he was in a much better mood about his Snow White animation being deleted after listening to the story of Pinocchio. And the animation on Jiminy Cricket would turn out to be some of Kimball’s best work. Although Kimball was never completely satisfied with Jiminy’s un-cricket-like final design, Frank Thomas defended it by saying that emphasizing the cricket-like qualities would have made him less human and therefore less loveable as a character.

After this, Kimball did the animation on Bacchus and his don-corn in the “Pastoral Symphony” segment of Fantasia (1940), an assignment Kimball didn’t enjoy as he would have preferred working with the hippos and alligators from the much more entertaining “Dance of the Hours” segment, but Kimball had much more fun animating the effeminate title character in The Reluctant Dragon (1941) and the crows in Dumbo (1941). Kimball did some outstanding work animating the crows dancing and singing the song “When I See an Elephant Fly.” For a scene that often gets derided for stereotypical caricatures of African-Americans, the crows deserve a much better legacy because they were excellent characters who were written with a lot of heart, and Kimball helped elevate them to the level of pure entertainment thanks to his amazing work here. This is the kind of animation that only Ward Kimball could do.

During the 1940s, Disney animators went on strike due to Walt’s reluctance to let them unionize. Kimball was the most left-leaning liberal of all of Disney’s animators, and therefore he was the only animator of the Nine Old Men who actually supported the strike, although unlike Art Babbitt and other strikers, Kimball remained loyal to Walt and did not quit, even though he knew it would be better if Disney unionized.

Kimball continued to do amazing work on The Three Caballeros (1944), with his greatest accomplishment being the title song sequence where Donald, José and Panchito go from one wild moment to another all while singing and dancing. Even Kimball himself saw this as some of his best work. The final scene where Panchito holds his note and Donald and José attempt to snap him out of it is a great example of pure Ward Kimball imagination.

Kimball also animated on the “Peter and the Wolf” segment and “The Whale Who Wanted to Sing at the Met” in Make Mine Music (1946), he animated Jiminy Cricket again in Fun and Fancy Free (1947) as well as Lumpjaw in the “Bongo” segment, he animated on “Blame It on the Samba” and “Pecos Bill” in Melody Time (1948) and various characters in both segments of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), but he started getting much meatier roles again in the 1950s, starting with Cinderella (1950), for which he was perfectly cast as the main animator for the mice and Lucifer the cat, bringing his own Tom and Jerry-like take to the cat and mouse rivalry in that film.

Alice in Wonderland (1951) was a Ward Kimball tour de force as he handled many of that film’s scenes, including the introduction of Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, almost every scene involving the Walrus, the Carpenter and the Oysters, as well as the Cheshire Cat (whose animation Kimball called “a masterpiece of understatement” when it came to depicting the feline’s subtle lunacy) plus the March Hare, the Mad Hatter and the Dormouse, whose wacky tea party scene really brings out Kimball’s love for vaudeville with an anarchy reminiscent of a Marx Brothers movie. I always found that scene to be the comedic highlight of the entire movie.

As brilliant as Kimball was at creating humorous and satirical animation, the other Nine Old Men felt he was not as good at sincere personality animation, something Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston excelled at, but this was just as well because it turned out Kimball began getting bored of the type of animation he was doing in the fifties. After animating the Lost Boys and the Indian Chief in Peter Pan (1953), Kimball test-animated the Siamese Cats for Lady and the Tramp, but his stylized design for the characters were deemed too out of place with the warmth that the movie demanded so it got vetoed.

Walt Disney, who was always good at utilizing the talents of his employees, assigned Kimball his own films to work on instead, including the acclaimed Disney shorts Melody (1953) and Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953), with the latter winning an Academy Award. With Ward Kimball in charge of the direction and being given creative control, his pent-up imagination exploded onto these two films. Kimball loved the creative freedom of directing and he embraced a more modern style that was closer to UPA than Disney.

Many fellow animators thought Walt would dislike those films but Walt was said to have totally bought into the films and Kimball’s comedic sensibility, and Walt assigned Kimball the job of directing the animated Man in Space segments on the Disney anthology TV series. The crew was also given a lot of free reign with these segments as Walt Disney was busy focusing less on animation and more on his theme park in the late fifties. In particular, Kimball directed 1957’s Mars and Beyond with his typical imagination, style and humor.

Walt would let Ward Kimball try directing a feature film next with the 1961 film Babes in Toyland, but that didn’t work out and Kimball got pulled out of that project and was relegated to animating Ludwig Von Drake in The Wonderful World of Color instead. Something Kimball did not relish but was great at nonetheless.

Kimball, his wife and his kids were all encouraged to be creative just like in the family he grew up with. He was not religious and would have no involvement in church, but he still had a big heart and was deeply affected by human tragedies such as the Vietnam War, even if he often masked it with humor. This led to Kimball self-funding an independent animated film called Escalation (1968) which made fun of politicians like Lyndon Johnson and was an underground hit with college students (who make fun of politicians regularly). But Kimball continued to work with Disney as well, animating the Pearly Band in Mary Poppins (1964), directing the Oscar-winning film It’s Tough to Be a Bird (1969), supervising the animated soccer match in Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) and producing and directing a half-hour TV series called The Mouse Factory which ran in syndication from 1972 to 1973 and showed clips from various Disney films cut together in a rapid-fire comedic manner that poked fun at the Disney image and featured such celebrity guest stars as JoAnne Worley, Don Knotts, Dom DeLuise and Phyllis Diller. The series was kind of like Laugh-In, but it didn’t really work and viewers and Disney executives rejected it after a single season. This led to Ward Kimball’s retirement in 1973, when he began to enjoy toy trains more than drawing.

A man of many talents, Kimball not only animated but he formed a dixieland jazz band called the Firehouse Five Plus Two, leading with the trombone (with animator Frank Thomas on piano). That band was actually successful at nightclubs, theaters and on network television. Plus, like I just said, Kimball was a big train enthusiast, going back to his earliest days in animation, creating the Grizzly Flats Railroad in his own backyard in 1938, and Kimball even helped Walt Disney rekindle his similar passion for trains, which was one of the sparks that led to Walt’s desire to create Disneyland. Walt always saw value in Ward Kimball’s sense of humor and eccentric style when it came to his contributions to Disney animation but Kimball was also one of Walt’s favorite people to spend time with and the two were close friends.

Often seen as the oddball of Disney animation, Kimball’s irreverent style of humor and things similar to it have since become much more commonplace in animation in the decades since Kimball worked for Disney, thanks to TV series like The Simpsons and The Ren & Stimpy Show and even Disney’s own films like Aladdin and Hercules. Kimball’s contributions to animation have also garnered a lot more respect since his retirement. And most ironically to many modern animation fans, Walt Disney was a huge supporter of Kimball’s independent spirit and often laughed at his jokes. So who’s to say Ward Kimball was un-Disney-like at all?